Pull out your wallet. Examine what’s inside. It might look like a bunch of paper and metal disks, but each bill and coin represents far more than purchase power. The imagery, phrases and symbols on currency tell vivid stories. From historical figures to national landmarks, money is a snapshot of a country’s identity. It doesn’t just define what something is worth – it reflects the aspirations of a nation – through its history, culture and ambition.

The Greeks were the first to recognize the power of coinage as economic and promotional tools. Earlier forms of currency were primarily functional; Greek city-states transformed coins into vehicles of propaganda. Greek coinage was carefully curated to evoke civic loyalty and pride while projecting strength and identity to the outside world. Coins became miniature billboards – a practice that would influence the development of most coinage throughout history.

The Romans inherited Greek culture, to include coins. They, too, considered them political platforms, but their assertions were distinctly Roman. Greek coins emphasized cultural and civic pride; Roman coinage validated imperial authority and military power. While Greeks presented local deities and heroes, Romans codified the ideal of Rome – a utopia worth dying for.

Celebrating military victories and triumphs, Rome broadcast its peerless power, promising vengeance to enemies and security for citizens. A marked departure from the local statements of Greek coinage, it reflected the vast empire – maintained through military might.

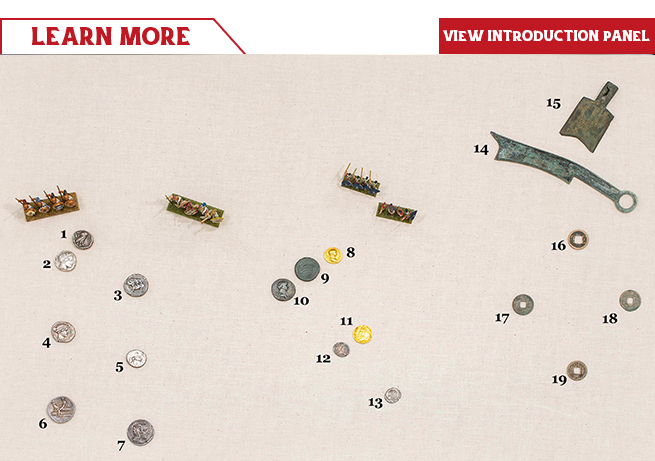

Traded across Eurasia, Western coins spoke to citizens and competitors. Chinese currency, however, took a very different path, unaffected by external cultures. The earliest currencies directly referenced value. Known as knife and spade money, they connected currency to daily life through literal depictions of common tools.

The first Qin emperor, Shi Huang (259-210 BCE), abolished earlier competing currency systems and introduced simple bronze coins with square holes – a design that persisted for two millennia. The bronze cash held little value compared to Roman coinage; Chinese currency was not designed for mass commerce or significant exchange. Instead, it was created for local, everyday transactions. Their value reflected the agrarian-based society, as well as the bureaucratic fear of portable, high-value currency, which could destabilize the status quo.

Unlike Western currencies, Chinese coins were cast – a speedier process that sacrifices detail and quality – which suited the Chinese economic philosophy. They made no attempt at propaganda; the government felt no need to legitimize itself. Cash coins were for internal circulation only. Therefore, basic, cost-effective coinage sufficed, remaining one-denominational until the 12th century!

A shared economic tool, coinage was the linchpin of Silk Road trade, allowing the exchange of dissimilar goods. However, each currency embodied their issuing empire, projecting distinct ideologies. The Greek drachm instilled civic pride. The Roman denarius broadcast military supremacy. Chinese cash restricted external exchange.

Now, back to your money. Can you decipher it? What messages does it relay? As you continue your trek along the Silk Road, consider how each culture employed and transformed currency for their own needs. Though a single medium, its purpose and ambition shifted with the hands that struck it.