World War I (1914-1918), also called “The Great War,” or “the War to End all Wars,” forever changed history. Unprecedented bloodshed on the battlefield was accompanied by social upheaval and revolution as ancient empires toppled and new nations were founded.

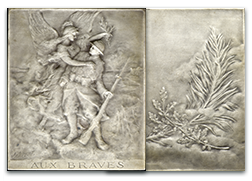

One of the most illuminating windows into understanding this period is through medallic art. Medals have been a popular form of artistic, commemorative and historical expression since the 15th century, so naturally they became important for expressing the events and emotions of World War I: patriotism, triumph, outrage, horror, loss, nostalgia and defeat. Medals were produced by all combatant nations during and after the war. There are several iconic medals remembered today, such as the iconic Lusitania medal, but the vast majority have been forgotten. This page presents many of these medals and gives a sense of what artists felt about the terrible calamity they experienced.

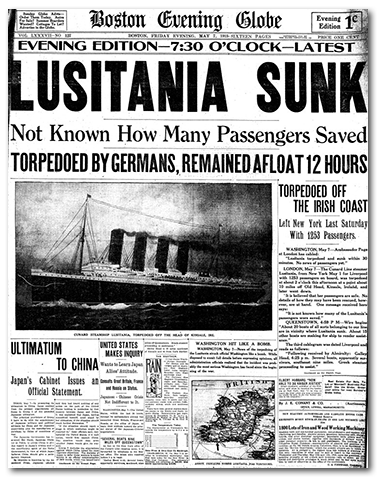

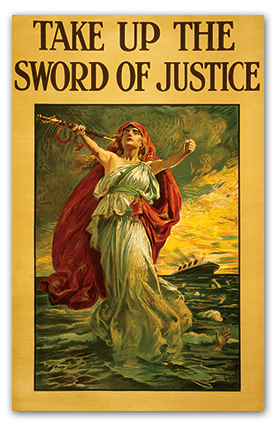

The RMS Lusitania

However, story of the Lusitania is complex. Prior to the sinking, Germany had declared the waters around the United Kingdom a war zone, and the German embassy in the U. S. had distributed warnings not to travel on the ship as it was suspected of carrying munitions and thus a legitimate target of war. British and American authorities falsely denied it was carrying munitions for decades after the war.

The British took advantage of the mistake to accuse the Germans of celebrating the murder of innocent civilians through the official government issue of the medal, even though Goetz was a private medalist. Britain used the inaccurate date as false proof that the sinking was planned in advance and that the medal, prepared in advance, was evidence of the plan.

Within months the British had produced thousands of copies of the Goetz medal (he only produced 180 originals) “proving” the barbarous nature of the German government. Goetz attempted to correct his mistake through the re-issue of the medal with a corrected date and by publishing explanations of his intent, but it was too late.

The Christmas Truce

As Christmas 1914 approached it was becoming clear that the war was not going to end soon. Troops were increasingly disillusioned with the horror and pointlessness of the fighting and were homesick – they had been promised a short war. Neutral American newspapers suggested that the combatants observe a “Christmas truce” to allow them to think about whether the war was worth the cost.

No official truce was called, but an unofficial truce did occur along parts of the Western Front between German and British units as soldiers fraternized, sang songs, exchanged gifts and food, and even competed in soccer games. Senior officers on both sides soon put an end to these demonstrations of goodwill so the business of war could go on.

Karl Goetz issued a series of annual medals from 1914 to 1918 commemorating the sacrifice of soldiers and celebrating Christmas. On each medal, a German military leader appears on the obverse, while the reverses depict one, two, three, four or five candles, symbolizing the year of the war. The first four medals have a legend translating to “Christmas on the field,” while the 1918 medal’s legend translates to “Christmas at home.”

Categories of Medals

The medals of World War I can be organized into categories: military awards, commemorative, satirical and propaganda. Military awards include medals for skills, accomplishments, bravery and participation. Commemorative medals range from commemorations of victories or individuals to memorials for damage and casualties. Satirical medals provide humorous or scathing criticisms of events during the war by artists and can blend into the category of propaganda medals designed to officially promote a specific view of the war. Below is a variety of medals from combatant nations on both sides.