Money as we know it was first conceived largely because its size and weight made it practical. Objects which ancient people agreed were of tradable value – livestock, crops, tools, etc. – were too large for convenient transport, and the emergence of coins simplified what it meant for people to acquire what they needed to live. Featured here are some of history’s largest and smallest currency – in size, weight and numerical value. All objects are on display at the Edward C. Rochette Money Museum.

Click on the images for an enhanced view.

Yap stone (or Rai stone)

ANA Collection 1989.141.5

Yap is a small island in the South Pacific known for gigantic, doughnut-shaped (for easier transport) limestone money measuring as much as 12 feet tall and weighing up to four tons. This example is more portable at 38 inches diameter and 90 pounds.

The most remarkable aspect of these massive pieces is that the limestone is not indigenous to Yap, but quarried and transported by canoe from the Palau islands about 250 miles away. The difficulty by which the stones were acquired gives them value. The stones have been used for hundreds of years to transfer wealth in social interactions such as marriage and political alliances, and are still used today.

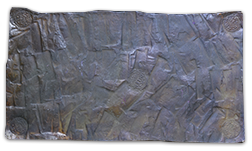

Swedish Plate Money, 10 Daler (replica)

ANA Collection 2016.100.683

Sweden became a major European power during the 17th century, but had no significant sources of gold or silver. However, Sweden produced two-thirds of the copper used in Europe, and in 1624 King Gustavus Adolphus began issuing large quantities of regular-sized copper coinage for domestic use, hoping that the decreased supply for export would increase copper’s price internationally and reduce the need for silver domestically. These copper denominations were too small for large transactions, but too large for convenience.

In 1644 Queen Christina issued a copper bullion “coinage” denominated in “dalers.” These massive copper “plates” ranged in weight from just over a pound to 52 pounds, and in denominations from a ½ daler (about 3.5 inches square) to 10 dalers (12.5 x 26.5 inches). Each piece was marked with stamps identifying denomination, mint, date and ruling monarch. Obviously, they were difficult to use and unpopular; the coinage was discontinued by 1776.

$100,000 Gold Certificate Specimen Notes

displayed courtesy of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Two uniface specimen $100,000 gold certificates – the largest denomination currency ever produced by the United States government. Ironically, these bills were released at the height of the Great Depression in 1934. The bills were never produced for circulation and were only issued for transfers between Federal Reserve banks, essentially replacing gold coins, which were demonetized in 1933. The notes feature President Woodrow Wilson. Only 42,000 were ever produced and the remaining examples are displayed at museums or held at Federal Reserve banks. The U.S. halted production of notes over $100 in 1945 and took them out of circulation in 1969.

2008 Zimbabwe 100 trillion dollar note

ANA Collection 2013.100.100

1993 Yugoslavia 50 billion dinar note

ANA Collection 2013.100.101

Both Zimbabwe and Yugoslavia abandoned these units of currency within a year of the notes’ issue due to rampant inflation. The largest denomination piece of paper money ever produced is the 1946 Hungarian 100 million billion pengő (100 quintillion) note.

India, Fanam, 14th-18th centuries, gold and silver (8 mm dia, .4 grams)

ANA Collection 2013.100.102-3

Obverse: Lion/various designs.

Reverse: Boar/various designs.

Some of the smallest coins ever produced were Indian fanams, gold and silver base-unit coins used for centuries. In the 17th century the Dutch East India Company produced large quantities of the coins.

Judaea (Alexander Jannaeus), Prutah or “Widow’s Mite,” 103-76 BC, bronze (17 mm dia, 1.2 grams)

ANA Collection 1996.37.2

Obverse:

(of King Alexander), around anchor.

Reverse: Star with eight rays.

In the Bible’s “Lesson of the Widow’s Mite,” Jesus tells the story of a poor widow gives two coins called “mites” to the temple. The coin seen here is an example of the small copper coins referred to as mites that circulated in Israel during Jesus’ time.

1851 United States Trime (three cent piece), silver

ANA Collection 2004.105.81

Obverse: UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; Union Shield within six-pointed star, date below.

Reverse: III (Roman numeral)/C; 13 stars around.

At 14 mm in diameter and only .8 grams, the three-cent silver trime (1851-1873) is the smallest and lightest United States coin ever produced. The coins were nicknamed “fish scales,” and were initially produced to simplify the purchase of 3-cent postage stamps. The larger nickel three cent piece was produced from 1865-1889.

1795 United States Half Cent, copper

ANA Collection 1981.0195.5466

Obverse: LIBERTY; Liberty facing left with freedom cap, date below.

Reverse: UNITED STATES OF AMERICA/HALF CENT/1/200; wreath around.

The smallest denomination of federal U.S. currency, half cents were produced by the Mint from 1793 to 1857.

1854 One Cent Note, City of Providence (obsolete, uniface)

ANA Collection 1976.4.126

The United States produced Fractional Currency (1862-1877) as an alternative to minting coins during a metal shortage caused by the Civil War. Fractional money was being produced by banks and cities well before the war, like this one cent note issued by the city of Providence, R.I. Small sized, small-denomination notes like these were called “shinplasters.”