The Assignat notes of the French Revolution were issued from 1790 – 1796. As with the Continental and State issues of the American Revolution, these notes as a whole are not especially rare, but they are tremendously important from a historical perspective because they illustrate a critical period of history. The ANA is fortunate to have a small group of these notes in the collection helping to highlight an otherwise obscure monetary experiment of the French Revolution.

The assignat originated in 1789 shortly after the start of the Revolution when France was threatened with insurmountable debt, and starvation and revolt in the countryside. King Louis XVI (1754 – 1793) convened the French Estates-General in order to find a way out of the crisis. The result was the creation of the National Constituent Assembly, tasked with resolving the public debt, and the beginning of the French Revolution. The tax system of the Ancien Régime with its innumerable, oppressive and unequally applied levies was abolished. Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (1754 – 1838), Bishop of Autun and later diplomat and politician, suggested the idea of nationalizing church property. With a total value estimated at 2 to 3 billion livres, this land had the potential to pay off the nation’s debt.

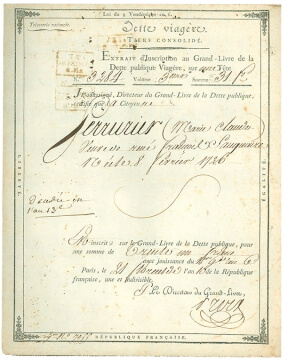

The problem was how to cash in on this potential source of wealth. The National Assembly decided to auction off the land, requiring that it be purchased with the newly created assignats, which had to be purchased with coins. Assignats were initially interest-bearing bonds issued by the French treasury backed by the value of the national lands (since they were mortgaged on or “assignée” to the value of the lands). Thus money was raised through the sale of the assignats regardless of whether or not they were used to purchase national lands. Since money was in short supply, the notes began to circulate as de facto paper currency.

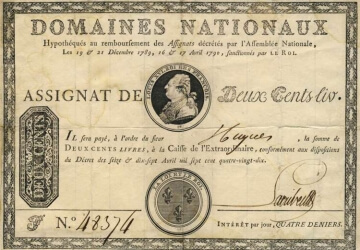

Paper currency was not new to France – it had been used for over a century with mixed results. After the disastrous “Mississippi Bubble” collapse of the 1720s, paper money lost favor among the French for many years. At the time of the Revolution the only paper currency was in the form of large denomination bonds and it had been decades since lower-denomination paper had circulated. The first assignats were authorized in December 1789 and issued in April 1790 bearing a 5% interest rate. The first issue consisted of 400 million livres in large denominations of 200, 300 and 1000 livres with detachable coupons.

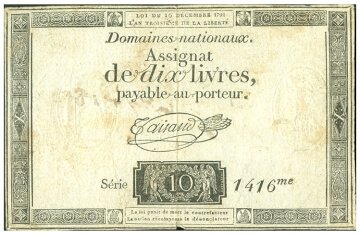

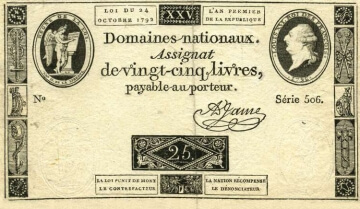

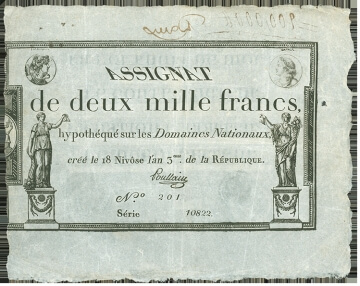

At first the assignats successfully stimulated the economy, but the shortage of circulating money for small transactions and the government need for still more money encouraged the Assembly to first lower, then eliminate the interest rate on the notes while simultaneously re-issuing instead of destroying them once they returned to the treasury. By September 1790, the assignat had become a true circulating paper currency, and 800 million livres worth of non-interest bearing notes were added to the initial issue, in denominations of 50, 60 70, 80, 90, 100, 500, and 2000 livres with legal-tender status. The lower denominations were produced in large numbers in order to ensure wide circulation. This change stimulated the economy but also increased inflationary pressures.

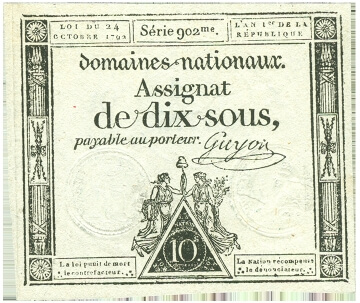

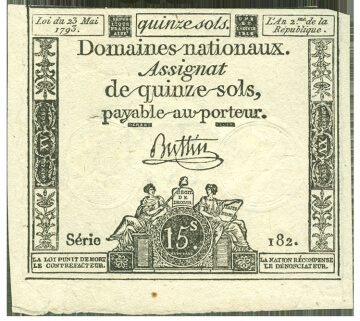

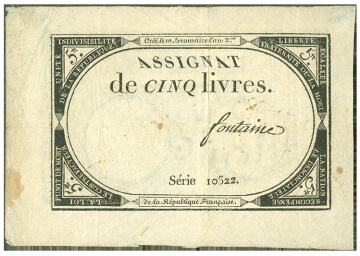

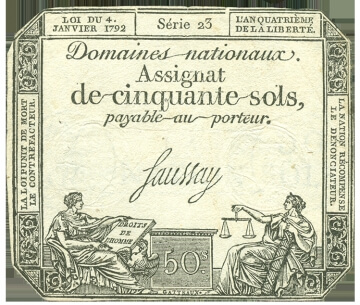

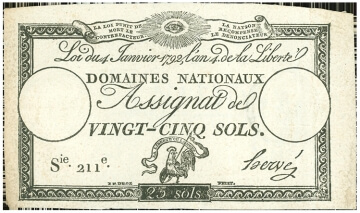

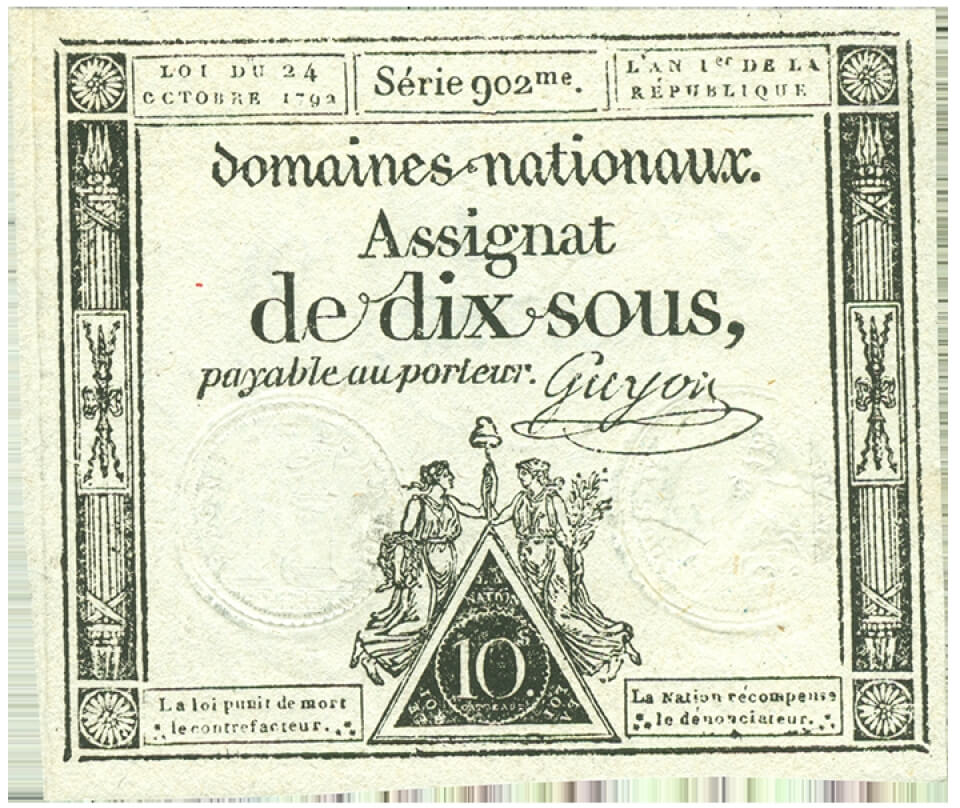

Meanwhile, coinage of all denominations had disappeared from circulation creating a crisis in small transactions that the National Assembly attempted to resolve through issuing more assignats, first in 5 livre denominations in May, 1791. By this time, assignats had begun to depreciate (in July 1791, they were worth 87% of their face value) as the government began to issue more and more of the notes (with over 1.3 billion livres issued from May to December 1791 alone!), but necessity forced the continued issue and use of the notes. In January of 1792 low-value assignats were issued in denominations of 10, 15, 25 and 50 sous to relieve the coin shortage and to replace the local paper issues that had become prevalent over the previous year.

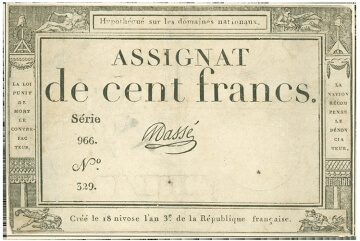

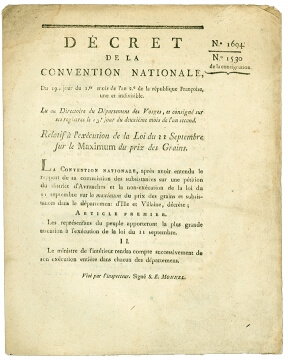

Then, in June 1791, the king attempted to flee France, setting in motion a train of events that would ultimately result in his deposition and execution and the end of the French monarchy. The immediate result was increasing pressure from abroad as England, Prussia, the Holy Roman Empire and Russia all reacted negatively to the imprisonment of Louis and the radicalization of the revolution. By 1792, the French Revolutionary Wars (1792 – 1802) had begun, increasing pressure on the economy and resulting in further inflation – eventually, after a short period of stability during the Reign of Terror ((July 1793 – July 1794), destroying the credibility of the assignat. By the end of their circulating period, assignats were worth only ¼ of 1 percent of their face value! The total face value of assignats had reached 45 billion livres by 1796 making them virtually worthless. The banknote plates for the assignats were symbolically burned in the Place Vendôme in February 1796. Its replacement by the short-lived ‘mandat territorial’ (land warrant) notes was unsuccessful, but, luckily for France, the success of the French armies abroad allowed for the reintroduction of metallic currency in 1797.

The assignats faithfully record the changes in the French government from monarchy to constitutional monarchy (October 1791 to September 1792) and to the 1st Republic (1792 – 1804) with changes in wording and design. Thus the early notes show the king’s portrait and state that they were issued under decrees of the National Assembly and sanctioned by him. On the notes, Louis is identified as the “King of the French” (Roi des Francois) rather than “King of France and Navarrre” and a cartouche showing the fleur de lys (lilly flower), symbol of the French monarchy, has the motto “The Law and the King” (Le Loi et Le Roi) marking the end of the old absolute monarchy in which the king was above the law. With the creation of the Constitutional Monarchy, in which the king was largely a figurehead, we see the introduction of the image of the allegorical genius of France writing the new constitution within the legend “Regne de la Loi” (Reign of the law) and, incidentally, the introduction of language specifying the death penalty for counterfeiters.

The new Republic introduced its own imagery and language designed to reinforce revolutionary messages beginning with the issues of September 1792. Simple linear designs feature allegorical figures and symbols including the eagle, fasces and liberty cap (symbols from the Roman republic), and figural representations of liberty, equality and justice. In the end, it was these symbols and messages that help spread the revolution to the people during it critical early years, assisting in destroying the old system of creditors and bondholders and clearing the way for reform. The assignat enabled the French Republic to survive and also provided the French peasants a means of purchasing land that they could not otherwise have acquired, taking the first steps in creating a rural middle class.

By Douglas Mudd, ANA Money Museum curator / museum director