A famous satirical bank note lampoons the Bank of England

What follows is a fascinating story of war, financial crisis, emergency legislation, government insensitivity, bank greed and social activism. A scenario from recent history, perhaps? Actually, this tale takes place in the late 1700s and early 1800s, when the flames of revolution engulfed France and eventually much of Europe.

The Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) witnessed conflict on a global scale, with the one constant being England’s refusal to accept French dominance in Europe. Britain stood steadfast against Napoleon Bonaparte’s imperial ambitions and despite repeated defeats was the financier of his continental enemies. This placed tremendous strain on the British Empire’s substantial resources, and Parliament was forced to enact emergency decrees to finance the endless wars.

In 1797 William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806), the prime minister (1783-1801 and 1804-06) who led Britain through the early part of the Napoleonic Wars, pushed a decree through Parliament known as the “Bank Restriction Act.” This legislation removed the requirement that Bank of England notes be exchangeable for gold or silver. The “restriction” ironically resulted in a huge expansion of paper money production as the government, businesses and individuals hoarded silver and gold. In conjunction with this new law, £1 and £2 notes were issued for the first time to make up for the coin shortage.

Monetary forgery was punishable by death at this time. Tragically, the law did not differentiate between forgery producers, distributors or handlers. Anyone caught with fake currency, even if they weren’t aware the bills were forgeries, could be executed. To compound this situation, the Bank of England hired a team of lawyers to ensure the law was vigorously enforced.

The result was a bloodbath. From 1783 to 1797, only four people were prosecuted for forgery – considered a white-collar crime. However, from 1797 to 1821, more than 2,000 prosecutions and 300 executions (about one-third of all executions during this period!) ensued, almost exclusively against citizens of the lower working class.

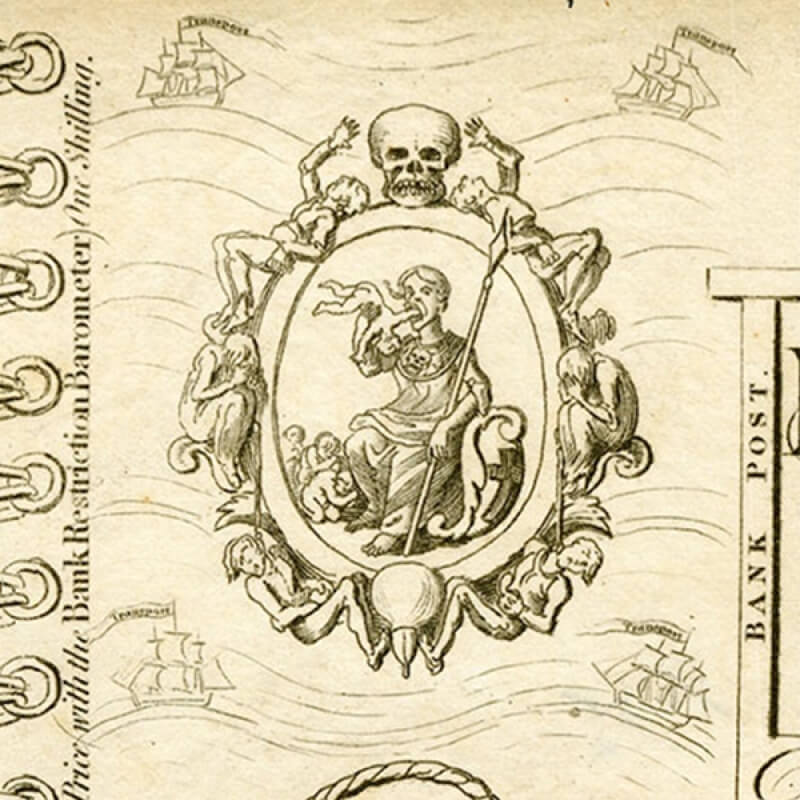

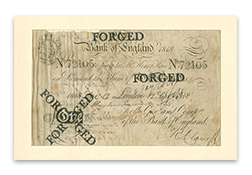

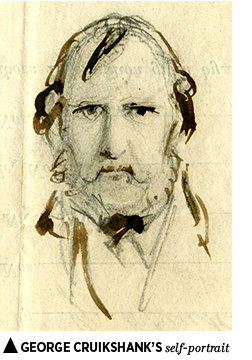

The Bank of England refused to improve the quality of its notes or change its punishments for forgeries. This incited public outrage, often expressed through caustic cartoons and pamphlets. In 1818 caricaturist and satirist George Cruikshank (1792-1878) designed a famous protest in the form of a satirical bank note that lampooned the Bank of England’s currency. Specimens were published by influential political satirist William Hone (1780-1842), and distributed to the Bank of England’s directors and the public.

The Edward C. Rochette Money Museum owns several objects related to this story, including a specimen of the Cruikshank note, a forged note that inspired his creation, his original sketch for the piece, and a copy of an article he wrote in 1876 about his role in ending the injustice. The device at left simulates a ledger binding. The upper left shows a cartouche with a caricature of Britannia eating her children, surrounded by ships labeled “Transport” (the contemporary term for exiling convicted criminals to places like Australia). A noose, tormented faces and a skull also appear.

The main scene at right depicts 11 men and women hanging from the gallows, with support beams on each side labeled “BANK POST.” Below is the provision “Promise to Perform/During the Issue of Bank Notes/easily imitated, and until the Resump/tion of Cash Payments, or the Abolition/of the Punishment of Death,” suggesting that the Bank of England was not concerned with the impact of its poor-quality notes nor the draconian application of the forgery law. As a final poke at the bank, the note is signed by “J. Ketch” – a 17th-century executioner notorious for botching killings using an ax.

The British government rescinded the Bank Restriction Act and resumed specie payments in 1821, making Bank of England notes convertible into coin. Though the severe laws were not changed until 1831, forgery prosecutions dropped drastically after 1821.

Cruikshank’s act of social activism helped galvanize public opinion and bring about change. In the final paragraph of his 1876 article in the Gloucester Chronicle, he writes:

In a work that I am preparing for publication I intend to give a copy of “The Bank Note,” as I consider it the most important design and etching that I ever made in my life, for it has saved the lives of thousands of my fellow-creatures, and for having been able to do this Christian act I am indeed most sincerely thankful.

View objects in the ANA’s collection in the gallery below.

Suggested reading:

The Life and Art of George Cruikshank, 1792-1878, the man who Drew the Drunkard’s Daughter, by Hilary Evans. RE35.C7E8.