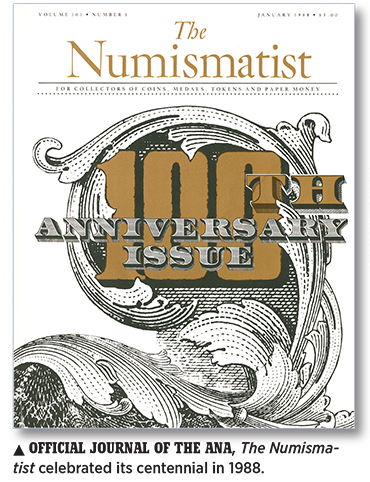

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the American Numismatic Association, of which you and I are proud members. Founded in Chicago in October 1891, the ANA has grown to include nearly 25,000 members and has become the world’s largest organization devoted to the history, lore and lure of coins, tokens, medals and paper money. Today, the ANA’s activities, educational programs and services are extensive and varied, including a museum and library, as well as conventions, seminars, online offerings and, of course, The Numismatist, which remains members’ primary benefit and source of Association news.

With this issue, I begin a series of monthly features about the history of the ANA, summarizing its progress and, along the way, its problems, potential and pleasures. This month, I offer a prologue— the pursuit of the hobby in America in the early days leading up to the debut of The Numismatist in 1888 and the foundation of the Association three years later.

The Early Years

The identity of the first serious numismatist in America is not known. Naturalist and American patriot Pierre Eugène du Simitière (1737-84) was active in the pursuit in the late 18th century. (Dr. Joel Orosz has researched Simitière and presented his findings in a study entitled The Eagle That Is Forgotten.)

In 1787 Wil liam Bentley, D.D. (1759-1819) of Salem, Massachusetts, entered in his diary some observations about coins in cir culation, creating one of the earliest such records known. He included the following in his notes for September 2:

About this time there was a great difficulty respecting the circulation of small copper coin. Those of George III, being well executed, were of uncommon thinness, and those stamped from the face of other coppers in sand, commonly called “Bir mingham,” were very badly executed. Beside these were the coppers bearing the authority of the states of Vermont, Connecticut and New York, etc., but no accounts how issued, regularly transmitted.

The Connecticut copper has a face of general form resembling the Georges, but with this inscription.…A mint is said preparing for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It may be noted that the New York and Connecticut coin face opposite ways.

The Connecticut copper has a face of general form resembling the Georges, but with this inscription.…A mint is said preparing for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It may be noted that the New York and Connecticut coin face opposite ways.

To remember all the coin which passes through my hands, I note down a few coppers of foreign coins, Swedish coin, shield, three bars, lion, etc., 1763, measures one inch and 3-10; another 1747, similar; Russian, a warrior on horseback with a spear piercing a dragon, on the reverse a wreath infolding a cypher.

Bentley’s diary entry on October 23, 1795, described his work with an important cabinet formed by another Salem collector:

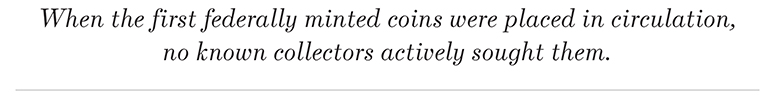

Busied myself to provide catalogue of coins for Mr. [Samuel] Curwen’s collection for Mr. [James] Winthrop. Such collections are rare in this country and in some parts utterly unknown. This is the largest that I have ever seen. The real antiques in silver, are an Athenian City, a Greek City, a Consul, Scipio, Juba, Julius Caesar, Augustus, Tiberius, Claudius, Hadrian, Marcus Antoninus. There are also a considerable number of copper and Mantuans, which the connoisseurs must distinguish. Among the modern is to be found a MARYLAND coin, Cecilius C Lord Baltimore. A Specimen is to be seen of all the modern coinage in this collection.

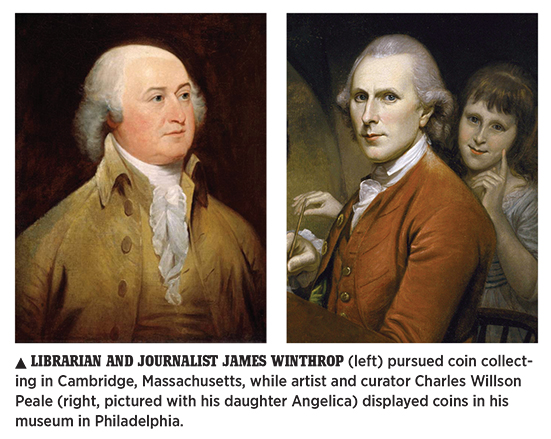

When the first federally minted coins—the 1792 silver half dismes—were placed in circulation, followed by copper half cents and cents in 1793, no known collectors actively sought them. Those who did pursue numismatics were mainly interested in ancient Greek and Roman issues, European coins and medals, and, to a more limited extent, Early American coins.

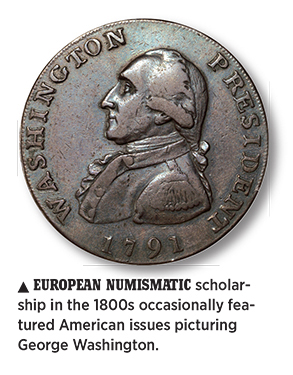

In Europe, numismatics was pursued by thousands of enthusiasts. In 1780s and ’90s England, many collectors searched for copper halfpenny-size tokens that circulated in commerce and sometimes were minted for sale to hobbyists. These pieces, known today as “Conder” tokens (after author James Conder, who cataloged them in 1798), featured many subjects, ranging from political figures and ruins of ancient abbeys to exotic animals, such as crocodiles and elephants.

Into the 19th Century

America’s interest in numismatics increased in the early years of the 19th century, mostly in the form of ancient and classical coins and medals acquired for their historical value. Young people who attended high schools and academies learned about ancient Greek and Rome as part of their studies, and most college students took Latin and sometimes Greek. Collecting related coins was a natural outcome.

Museums were opened in many cities, some as part of historical or learned societies, and others as attractions for the admission-paying public. Coins and medals usually were on display. Few inventories with content useful to modern-day numismatists have survived.

In the meantime, money was often mentioned in newspaper and magazine articles, notably curious instances in which buried silver and gold pieces came to light. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a charming story about the master of the Massachusetts mint who paid his daughter Betsey’s dowry in her weight in newly coined Pine Tree shillings. In 1821 John Allan, a Scottish immigrant, bought and sold coins while engaging in his occupation as an accountant. In that decade, Philip Hone, mayor of New York City, lived nearby and was among Allan’s clients, as was Baltimore numismatist Robert Gilmor Jr.

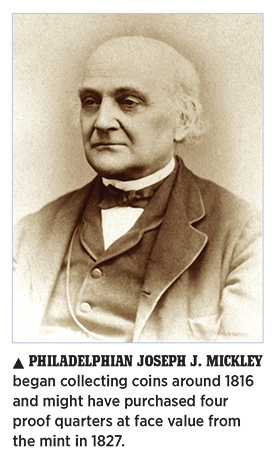

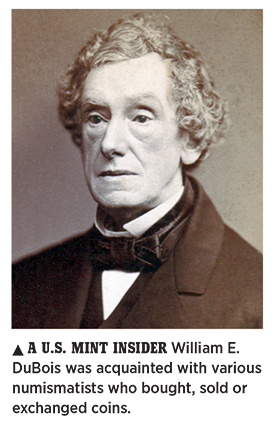

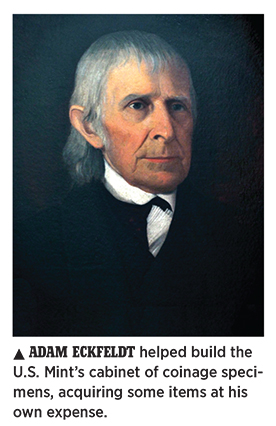

The Mint cabinet was authorized by Congress in July 1838. In time, co-curators William E. DuBois and Jacob R. Eckfeldt formed a fine collection (much of which resides in the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution, to which it was transferred in 1923). Prior to 1838, Adam Eckfeldt (1769-1852), who had been at the mint since its inception and was guided by “his own taste and the expectation that a conser vatory would some day be established,” began a collection of rare and unusual foreign coins (deposited for recoinage) and of select specimens of U.S. coins (assembled at his own expense). This included an 1822 half eagle (gold $5) retrieved from a bullion deposit.

The March 1852 issue of Banker’s Magazine noted Adam Eckfeldt’s passing:

THE MINT. – Mr. Adam Eckfeldt, formerly chief coiner of the Philadelphia Mint, died on Friday, February 6, in the eightythird year of his age. Mr. Eckfeldt has long been a well-known and highly respected citizen ofPhiladelphia. He began to make machinery for the Mint at its first organization in 1792-3; was soon after appointed assistant coiner, and in the year 1814 was made chief coiner, which office he held until the year 1839, at the age of seventy. As a special token of regard, his fellowofficers presented him on that occasion with a gold medal bearing his likeness. Nearly all the coinage of the country, up to 1839, was executed under his immediate superintendence; and by his ingenuity several valuable improvements were made in the machinery and processes, some of which were afterwards adopted in foreign mints. The son of Mr. Eckfeldt is now one of the assayers at the Mint.

In 1839 the first numismatic book was published in the United States: An Historical Account of Massachusetts Currency by Joseph Felt. Remarkably, its information is still useful to today’s collectors, if you are lucky enough to obtain a copy!

The 1850s

In 1851 the first American numismatic auction of any importance featured the estate collection of Dr. Lewis Roper. He had gone to California to take part in the Gold Rush, but he became very ill and died aboard a steamship during his return trip.

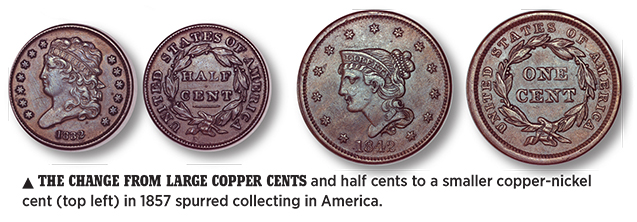

The public’s interest in numismatics grew after the Coinage Act of February 21, 1857, discontinued the copper half cent and cent, and authorized the new, small coppernickel cent. A wave of nostalgia swept across the land. Thousands of citizens began to save the “pennies” of their childhood, and some set about acquiring as many different dates as possible. Their enthusiasm knew no bounds.

Historical Magazine was established that year and went on to include many articles about coins. Norton’s Literary Letter was another source of information. In Boston, Jeremiah Colburn wrote articles about coins for a local paper, and in New York City Augustus Sage did the same. The Philadelphia Numismatic Society was organized in the waning days of 1857. In March 1858, Sage, then a teen aged school teacher, gathered collectors in his family’s apartment upstairs at 121 Essex Street in New York City and formed the American Numismatic Society. Similar groups were established within the next several years.

In 1858 Sage cataloged three r

In the American series, the most actively sought items included colonial and related coins dating back to the Massachusetts silver issues of 1652; tokens and medals of George Washington (the hottest items by far); copper cents dated 1793 and later; silver coins from 1794 to the late 1830s; gold coins from 1795 to 1834; and medals with American themes.

Later Years

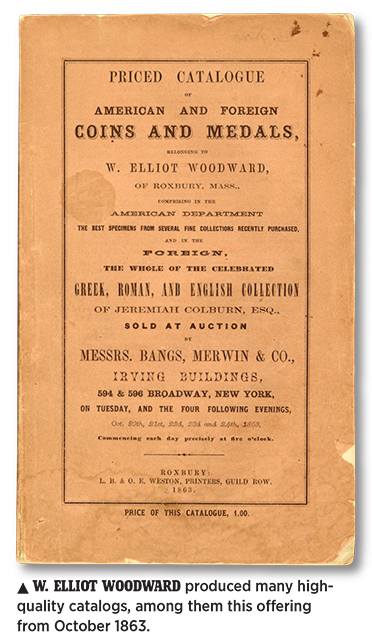

In the 1860s, the hobby matured somewhat. W. Elliot Woodward of Roxbury, Massachusetts, operated a pharmacy and, as a sideline, cataloged rare coins for auction. An intellectual par excellence, he was well studied and had a large library. Competition was furnished by Edward D. Cogan, an English immigrant who operated an art shop in Philadelphia. In 1858 Cogan sent out letters offering copper cents to mail bidders. Based on this, he later boasted he was the father of the rare-coin trade in America, a false premise as several others were in the auction field as well.

For reasons not known today, the American Numismatic Society either slipped into a coma or died in 1860. In 1864 collectors (not involved earlier in the ANS) formed the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society in New York. The ad dition of “and Archaeological” was an effort to broaden membership. It soon became obvious that fossils and dinosaur bones were of little interest to numismatists, and archaeologists did not care that the 1787 Columbia and Washington medal was rare. Years later, the name was changed to the American Numismatic Society. Today, the ANS—headquartered on Varick Street in New York City—is dynamic.

In 1883 the Shield-type 5-cent piece was discontinued, and the Liberty Head nickel, designed by Charles E. Barber, took its place. The denomination on the reverse was stated simply with the Roman numeral “V,” a logical move since the 3-cent piece was identified as “III.” Fraudsters seized upon the nickels, gold-plated them, and passed them off as $5 gold coins of similar diameter. This necessitated a quick change, and the word CENTS was lettered on the reverse. A nationwide sensation was created when it was publicized that any 1883 nickel without CENTS would be recalled by the mint and likely become a valuable rarity. Tens of thousands of excited treasure hunters joined in the search. So many CENTS-less nickels were saved that today they are the most common Liberty Head nickels in high grades.

Nevertheless, thousands of people were captured by the lure of numismatics and stayed on to become collectors of other things. This engendered the most dynamic rare-coin market in history up to that time. Coin auctions were held at the rate of about one a week, countless catalogs were issued, new magazines were published, and many dealerships were established.

Making its debut on the coin collecting scene in the autumn of 1888 was The American Numismatist, a modest four-page leaflet dated September-October, the brainchild of George F. Heath, M.D. of Monroe, Michigan. The doctor was an intellectual in the mold of W. Elliot Woodward. He had his eye on the future, with more issues planned, as the masthead proclaimed that the initial edition was Volume 1, Issue No. 1.

Thus was planted a seed that, in 1891, would germinate and result in Dr. George Heath’s creation of the American Numismatic Association, setting the scene for next month’s chapter.

Last month, I profiled the early years of numismatics and the establishment of the hobby in the United States, which led to the eventual publishing of the first issue of The American Numismatist. This month’s installment will discuss the formation of the American Numismatic Association and the man behind the magazine, Dr. George Francis Heath.

George Heath, M.D.

Heath was born on September 21, 1850, in Warsaw, New York. When he was 10 years old, his mother died and he was sent to Poultney, Vermont, to live with an uncle. In 1861 his father joined the Union army.

Heath moved to Warrensburg, Missouri, in 1871 where his father had established residence. There he continued his education, including advanced placement in the State Normal School. By 1872, Heath was appointed postmaster of Warrensburg, a position he held until 1876, at which time he resigned to pursue a career in pharmacy. That same year, he married Lucy May Rayhill, a Warrensburg native. He also served two terms as a town councilman. Heath’s pharmacy career engendered a desire to learn more about medicine, and in 1879 he entered the University of Michigan. While there, he served as president of his class. He graduated with a medical degree in 1881, and was appointed resident physician and surgeon at the university hospital, where he and his staff attended to about 5,000 cases over the next three years.

In 1884 Heath and his wife moved to Monroe, Michigan, so he could take over Dr. C.T. Southworth’s practice. Once there, Heath engaged in many activities, including those related to charity, education and politics, the last capped by his election as mayor in 1890, after which he served multiple terms. He also pursued many hobbies, including coin and stamp collecting, and traveling by rail to destinations he considered interesting. An avid reader, Heath’s personal library comprised over 1,000 volumes.

The Numismatist

In Autumn 1888, Heath (who nearly always gave his first name in print as “Geo.”), published a fourpage leaflet titled The American Numismatist. Dated September-October, the pamphlet’s masthead read “Vol. 1 …No. 1.” Obviously, an extensive future was planned.

Apparently unknown to Heath, C.E. Leal of Paterson, New Jersey, had launched a magazine, also titled The American Numismatist, in September 1886, predating Heath’s periodical by two years. Although Leal changed the name to The Collector’s Magazine in early 1888, Heath changed the name of his publication’s second issue to The Numismatist, the name it bears today.

For the next several years, the magazine contained a variety of news articles, advertisements and coin features, and Heath sold American and world coins in each issue. More than anything else it was a house organ. In the first issue, for just 60 cents the reader could order: “Packet No. 13, contains 10 var. of silver coins size of half dime,” or for $1.25 Packet No. 14 “contain[ing] 10 var. of same dime size.” Heath also had this to say in the first edition:

Of one thing all may rest assured, this paper has come to see its year out and though small and unpretentious, will, like the Irishman’s flea, ‘get there just the same,’ and when least expected. And so without further ado we launch our frail bark on the journalistic seas, and with clear skies and a flowing sail go out on our mission.

The Numismatist was not without its problems. From the late 1880s into 1890, the nation was in an economic recession, and some subscribers dropped out. Heath wondered if the magazine would endure, but after some fits and starts, it did.

A Memorable Proposal

In 1891 on a sunny day in Monroe, Michigan, Heath announced that The Numismatist would be issued twice monthly at an annual subscription rate of 50 cents.

Every number will be illustrated. Every number will contain interesting articles and notes on coins. Every number will contain the names and addresses of from 10 to 15 or more live coin collectors, with their specialties, if any.

In February of that year, Heath went on to say:

What’s the matter of having an American Numismatic Association? Would it be possible? Would it be practicable? All in favor of such a scheme, send in your names. If a sufficient number are received, we can think of organizing on some inexpensive basis.

The seed was planted, and Heath furthered the idea in the March 1891 article, “A Plea for an American Numismatic Association.” Through the publication of this editorial, the good doctor found many individuals who might contribute to the success of such an organization.

Wheels in Motion

Not one to deal in theory when practice could be accomplished, Heath took the bull by the horns, and in the July 1-15, 1891, issue of The Numismatist he said that the American Numismatic Association was a necessity. No doubt about it! Henceforth, he nominated those whom he hoped would serve on the board if the ANA was formed:

For president: W.G. Jerrems, Jr., of Chicago; vice-president: Joseph Hooper, Port Hope, Ontario; secretary: Charles T. Tatman, Worcester, Massachusetts; treasurer: David Harlowe, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Board of Trustees: C.W. Stutesman, Bunker Hill, Indiana; W. Kelsey Hall, Peterborough, Ontario; J.F. Jones, Jamestown, New York; Board of Temporary Organization: George W. Rode, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; J.A. Heckelman, Cullom, Illinois; F.J. Grenny, Brantford, Ontario.

“These officers nominated are all tried and true, and earnest workers in the numismatic field,” said Heath. “We do not expect one will shrink from duty. If for good and sufficient reasons he cannot serve, at least hold the picket line until the relief comes up on permanent organization.”

Call for Convention

In the August 1-15, 1891, issue, Heath speculated that there might be as many as 20,000 coin collectors in the United States,

of which it is probable that less than 5% collect scientifically or intelligently; about 40% are still in the “medieval” age, and the balance just emerging from the “barbaric” state. To these varied classes will the Association appeal.

He reported that 25 members signed up for the ANA as of July 1, 1891, and “many more” were waiting until the organization became official.

The September 1891 issue (combined numbers 17 and 18) stated that the Committee on Temporary Organization of the American Numismatic Association had called for the first convention to be held in Chicago on Wednesday, October 7, 1891.

We hope all will attend that can possibly do so, and that the First Convention of the ANA may be a success in every particular. With two-thirds of our membership in the East, and an infant organization besides, there may be some who may doubt the propriety of calling the convention so far from the majority. We however trust that the result will show that the Committee acted with wisdom in this matter. The holding of the convention in Chicago should bring in a number of additions to our association from the Windy City and vicinity…

Heath announced that from October 1 through 7, he would be at the Commercial Hotel, at the corner of Lake and Dearborn Streets, in Chicago, preparing for the event.

ANA Formation

The convention took place, and all transpired as Heath hoped. He later reported that the Board of Officers of the American Numismatic Association had been elected, with the top nominees earning seats. Additional officers included Librarian and Curator S.H. Chapman; Superintendent of Exchange George W. Rode; and Counterfeit Detector Ed. Frossard. The Board of Trustees consisted of W.K. Hall, C.W. Stutesman, J.A. Heckelman, J.F. Jones and H.E. Deats.

We were in at the launching and saw the good ship Numisma go out with flowing sails and a clear sky on her 12 months voyage. Sixty souls comprise her officers and crew. Monthly stops will be made and passengers received. Numismatists! This Ark has been fitted out with special reference to your comfort and convenience. Make haste and come aboard, an awful shower is coming up.

Two days were spent in a pleasant and harmonious convention; a constitution and bylaws were adopted, that, while not perfect, we believe will serve the Association well. Thirty-one members were present in person, or represented by proxy.

Heath stated that members could join the ANA by paying an initiation fee of 50 cents and submitting a form signed by two members of the organization. If no objections were received within 30 days of the date of publication in the journal, the secretary would issue a certificate of membership signed by the president.

It was apparent that The Numismatist was becoming the official journal of the ANA (although this was not specifically stated), and as recently as the November 1891 issue, it was intimated that Plain Talk was still in the running for this honor.

The First Year

During the Association’s first year, The Numismatist expanded in size and coverage. Advice on collecting and how to clean coins, plus auction news, biographies of collectors and dealers, and other content made the magazine a key source of information. In the meantime, the American Journal of Numismatics, launched in New York City by the American Numismatic and Archaeological Association in 1866, was now published in Boston. A typical issue featured research information, auction news, and other content, and was more scholastic in nature than the popular style employed by The Numismatist.

Coin grading, still controversial today, was first discussed at length in The Numismatist in February 1892. Joseph Hooper, a frequent contributor, suggested a system based on Roman numerals from I (“Brilliant Proofs or first strikes on planchets”) to XII (“Very Poor”). As printed descriptions in auction catalogs and other publications varied all over the place throughout the United States, Hooper suggested such a system would make grading understandable to everyone.

At this time, there were 80 ANA members and 411 subscribers to The Numismatist, still privately published by Heath. This changed after 1892, when Heath wrote, “If desired, The Numismatist with its prerequisites and emoluments will be turned over to the Association.”

Among news of the era, it was stated that ANA Trustee Hiram Deats, a well-known figure in the hobby, had dropped numismatics in favor of stamp collecting, and his coins would be sold at auction by Ed. Frossard. Not long before, in 1890, Lorin G. Parmelee, who had built what was probably the second finest collection of United States coins (after T. Harrison Garrett’s) and consigned it to the New York Coin and Stamp Company for auction, when the economy was struggling, “bought in” many items. Finally, in early 1892, Parmelee sold the remaining items for $75,000 to William Sumner Appleton, a prominent Massachusetts collector.

The Scott Stamp and Coin Company was located at 12 East 23rd Street in New York City and staffed by 19 people, probably the largest dealership in the country. At the time, most coin dealers also sold stamps, and many offered autographs, fossils, Indian arrowheads and artifacts, and even birds’ eggs. In Philadelphia in 1878, brothers S. Hudson and Henry Chapman partnered to form the leading auction company. The duo, born in 1857 and 1859, respectively, learned the trade as employees in J.W. Haseltine’s shop in the mid-1870s.

In 1892 it was proposed that the second annual ANA convention be held in Niagara Falls. Little information was published about the event, and only five people attended, including Deats, who, it seems, concluded that collecting coins was a nice hobby after all. Another convention (this one better publicized) was scheduled for Pittsburgh on Saturday, October 1, 1892. None of the officers attended, although 36 members were represented, mostly by proxy (a very controversial policy that endured for decades). Henry McKnight volunteered to preside, W. Rode took notes in the absence of the secretary, and Heath was elected president of the ANA.

An Uncertain Year

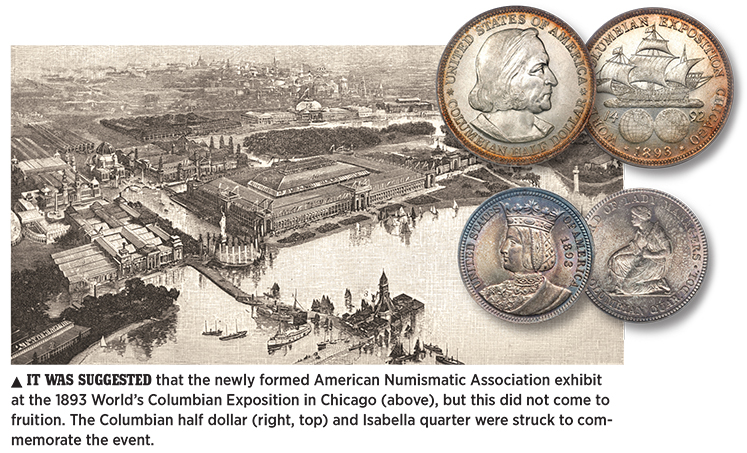

In 1893 expanded coverage was given to the World’s Columbian Exposition and its coins. The Panic of 1893, as it was later called, negatively affected the economy, which had improved more or less since the Civil War. By the late 1880s, vast growth in the prairie states, largely financed by Easterners buying bonds that paid 8 percent or more annual interest, slowed, and many bankruptcies occurred.

In a special message in the March issue, Heath reassured readers that the ANA was here to stay, but many difficulties loomed ahead, including apathy within the ranks. “However, once the Valley of Despond is crossed, the Delectable Hills are ahead,” he stated comfortingly. Each member was encouraged to spread the word about the Association among friends, acquaintances and correspondents. Still, there was doubt:

Stand by the guns! If by any possibility our ship goes down, let it be like the Cumberland, with our guns trained and booming and our flag flying. We have set our mark high. If we fail to realize all our hopes and ambitions we shall still be found fighting in a worthy cause; as success crowns our efforts, and we expect nothing else, to our science and Association give the glory.

(The above suggests that mostpeople who read Heath’s articles would have done well to have an encyclopedia at hand. Few probably could remember the fate of the U.S.S. Cumberland.)

The March 1893 issue of The Numismatist also shared a variety of interesting facts: President William Henry Harrison possessed a collection of ancient Greek and Roman coins; only five 1815 half eagles were known; the King of Sweden paid $2,000 to complete his set of U.S. coins; the rarest coin in the U.S. series was the double eagle of 1849; only 10 1804 silver dollars were in existence; and a Fine half dime of 1802 was worth $100.

The “Slough of Despond” continued, as per Heath’s April editorial, again in his inimitable style:

For now, upwards of two years, we have endeavored to keep alive the flame that faintly flickered on the altar in the temple dedicated to Numisma. In the midst of a busy professional life we have been glad to do this little, though it has crowded our spare time to the utmost. Many times we would have been glad to lay our burden down or place it into worthy or abler hands; but we have found no opportunity. We see none now…of our trials and hindrances, of our doubts and disappoinments, none may know…and yet, there have been rifts of sunshine through the shadows to lighten our burden and make glad our way. To those friends who have by their aid and subscriptions, contributions, advertisements, kind words, etc. do we extend our heartfelt thanks. By your aid we have done what we have done … our future, to make or mar our superstructure, lie mainly with you.

Meanwhile, Augustus G. Heaton published Mint Marks, a booklet that gave 17 reasons why collecting coins by mintmarks rather than obverse dates was a good idea. This suggestion caught on, but it was not until the next century that the practice became accepted widely.

The Association’s annual convention was held in Chicago on August 21 so at tendees could visit the Exposition. Fifteen members took advantage of the opportunity. The event was held at Douglas Hall, and the official program noted the presentation of 12 different scholarly papers.

Onward & Upward

The January 1894 issue of The Numismatist included a poem by Heaton titled “The Convention of the Thirteen Silver Barons.” The “barons” in question consisted of rarities in the American silver series, with the 1804 silver dollar being the “chairman,” and the others consisting of the 1802 half dime, the 1804 dime, quarters of 1823 and 1827, half dollars of 1796 and 1797, and dollars of 1794, 1838, 1839, 1851, 1852 and 1858. The lengthy and clever poem was a commentary on the unrestricted coinage of silver.

In the April 1894 column, “Hooper’s Restrikes,” which had appeared intermittently during the preceding year, included this:

Coin collectors have long felt great difficulty in making a complete collection of American specimens. The United States coinage of 1793 is very rare, and a dollar of the year 1794 has often sold for as much as $100. The 1796 half cent is so rare as to readily sell for $15, and a half dollar of the same year is worth 60 times its original value. While the half cent of 1804 is common enough, all the other coins of that year are rare, the dollar of that particular date being the rarest of all American coins. Only eight are known to exist out of the 19,570 that were coined. The lowest price that one of these now changes hands for is $800.

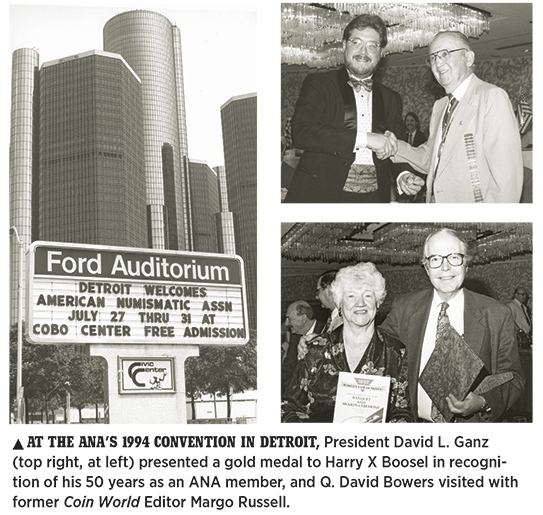

In August 1894, the annual ANA convention was held in Detroit. It was reported that 191 people were ANA members in good standing. Of that number, the division by states was as follows: Massachusetts and Michigan led the pack, each with 24 members, followed by New York with 20, then Pennsylvania (16), Illinois (14), Indiana (10), Rhode Island (7), New Jersey (7), Wisconsin (6), Nebraska (5), Ohio (4), Connecticut (4), Iowa (3), North Carolina (3), New Hampshire (3) and Virginia (3). Several other states had one or two each, and about twodozen members were located in foreign countries. Among those attending was young Howard R. Newcomb, a native of Detroit, who in later years would become one of the most prominent people in the hobby.

During this era, Heaton’s series “A Tour Among the Coin Dealers” attracted wide attention. Separately, his remarks on certain behind-the-scenes activities at auctions stirred up controversy. The grading of coins continued to be a popular subject for discussion, with few conclusions reached other than that there should be some kind of grading system.

ANA membership was growing steadily, and by March 1895 it was reported that the latest person to join the roster, C.H. Porter, of Winona, Minnesota, was assigned number 241. However, there were some vacancies among earlier numbers, and quite a few members had not renewed their dues. The annual convention was held in Washington, D.C., that summer.

In December, Heath was criticized sharply by Lancaster, Pennsylvania, dealer Charles Steiger walt, who said the ANA was wasting its money by publishing The Numismatist, as it was of no real value. Unstated was that Steigerwalt had recently launched his own magazine. By that time other dealers also had been critical, with some stating the magazine was revealing names of private individuals and information that should not be made public.

Quiet Times

In 1896 the hard-fought U.S. presidential contest of that year, which pitted Democrat William Jennings Bryan, an advocate of free and un limited coinage of silver to benefit Western interests, against conservative Republican William McKinley, spawned many varieties of anti-Bryan medals that became widely desired as collectibles. The ANA convention was advertised to take place in Philadelphia on September 18 and 19, but later was canceled. Heath voiced his frustration, stating that

up to the time the manuscript of this issue is given to our printer (August 27) no communication has been received from the officers of the Association further than has been published in these pages. We know no more regarding nominations, election and place of meeting than before.

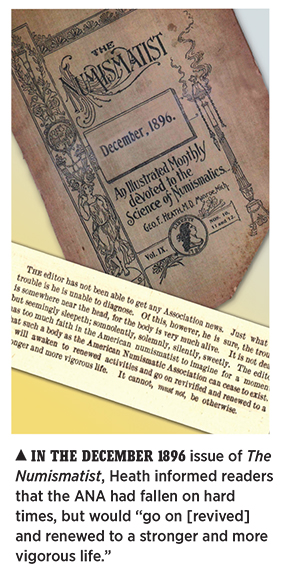

the editor has not been able to get any Association news. Just what the trouble is he is unable to diagnose. Of this, however, he is sure, the trouble is somewhere near the head, for the body is very much alive. It is not dead, but seemingly sleepeth; somnolently, solemnly, silently, sweetly. The editor has too much faith in the American numismatists to imagine for a moment that such a body as the American Numismatic Association can cease to exist. It will awaken to renewed activities and go on revivified and renewed to a stronger and more vigorous life. It cannot, must not, be otherwise. This magazine cannot, however, afford to remain with the inactive body longer, and until it arises with new habiliments and energy, shall remain detached and independent. In the meantime its efforts shall be toward resuscitation.

Thus, at the end of 1896, the editor and owner of The Numismatist

informed readers that it was no longer the official journal of the

Association. The ANA remained in suspended animation—or was it dead? No

one knew for sure.

Vive le Association!

In August 1897 Heath printed a letter from J.A. Heckelman, president of the Board of Trustees, which invited members to vote for new officers. This was all that was needed to revive the Association. Heath took up the fallen banner of the ANA and exclaimed, “Vive le Association!” The Numismatist resumed as the organization’s official publication.

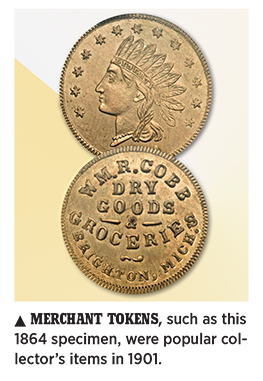

In January 1898, a lengthy series titled “American Store or Business Cards” by Dr. Benjamin P. Wright made its debut. This catalyzed interest in such tokens to the extent that, for the next decade, they would be the hottest tickets in the numismatic market.

In April it was reported that the ANA had over 250 members. The Spanish-American War of 1898 resulted in various medals that were featured in The Numismatist as they were issued. No convention was held this year. The only successful annual gathering after the ANA’s formation was in 1894 in Detroit. The others were failures, according to Heath.

On December 14, 1899, the centennial of George Washington’s death, Lafayette commemorative dollars dated 1900 were struck by the Philadelphia Mint. As the ANA and the hobby of numismatics headed into 1900, the cusp of the new century, everything was looking up. The American economy had recovered, and the ANA was dynamic once again.

As relayed in this series last month, the 1890s were challenging for the ANA. After the enthusiasm of its founding in 1891, the growth of membership, and a successful convention in Detroit in 1894, the Association slowed down. Not helping matters was the economic recession following the Panic of 1893, which resulted in many bankruptcies and a slow coin market. At one point, ANA officers were not answering correspondence or providing information to Dr. George Heath, Association founder and editor of The Numismatist. Happily, things took a turn for the better later in the decade, and by 1900 The Numismatist once again was filled with news of Association activities.

By 1901, the market had perked up. Among the hottest tickets were merchant tokens and storecards inspired by a serialized study by Dr. Benjamin Wright featured in the Association’s magazine. Most merchant tokens were inexpensive—no more than $3 apiece for hundreds of varieties. Hard Times tokens, mostly the size of the large copper cents issued in 1832-44, were in the fast lane as well, catalyzed by a popular book, Hard Times Tokens, by Lyman H. Low (ANA Library Catalog No. PA73.L6).

Leading off in the January 1901 issue of The Numismatist was an article by George W. Rice, “The Copper Cents of the United States,” which gave an overview of the work of Sylvester Sage Crosby, Francis Worcester Doughty, Ed. Frossard and William Wallace Hays, and their descriptions of cent dies. “The copper cents have ever been in favor with the United States collectors, and probably more sets of them are being formed than any other coin, with a consequent effect on values,” Rice wrote.

Although this might seem strange to read today, there was hardly any interest in collecting United States coins by mintmark varieties in 1901, even though Augustus G. Heaton’s 1893 Mint Marks (GA80.H4) treatise was widely sold. Probably fewer than a dozen or so numismatists collected branch-mint Morgan silver dollars. Instead, these and other coins were acquired by date, and current proofs served to fill that need. Even so, interest in proofs was much lower in 1901 than it had been in the mid-1880s. More people collected Hard Times tokens by varieties than collected Seated Liberty and Barber coins or Morgan dollars by mintmarks.

In 1901 The Numismatist announced that Joseph Lesher was planning to issue 10,000 souvenir “Referendum dollars”: “The silver will cost him $6,500, and the making $1,500. He will sell the coins for $12,500 and redeem them on demand for the same amount.” Today, a single “Lesher dollar” in high grade is valued at four figures. The byline of Farran Zerbe, a peripatetic young entrepreneur from Tyrone, Pennsylvania, appeared in various articles of the era, with no hint that by decade’s end he would create unprecedented controversy. The 1901 ANA convention was held that August in Buffalo, New York, as part of a schedule more occasional than annual. The venue was the medical office of ANA President Benjamin Wright, M.D. A woman named V.H. Eaton came into the convention, and the receptionist thought she was a patient. Amazingly, she was there as a collector—unprecedented in a hobby that most people thought was reserved for men.

At the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo on September 6, an assassin shot President William McKinley. He was treated nearby, and a young part-time coin dealer, Thomas L. Elder, appointed as the official government telegrapher, relayed news of the president’s condition to the world until McKinley’s death on September 14.

Heath reminisced that, of the 61 ANA members active in its founding year of 1891, only 16 remained by 1901. During the year, 119 new members signed up, of whom 14 were age 50 or older. The average age was 381⁄2 years, with the youngest being 13 and the oldest 60.

In early 1903, the ANA roster comprised 450 names. The coin market was strong, and the American economy was growing. Zerbe landed a contract as the official distributor of the first American gold commemoratives—two varieties of gold dollars dated 1903. One depicted the late President McKinley, and the other featured Thomas Jefferson, who had negotiated the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. These coins were offered for $3 each, raising howls of protest from collectors and dealers. Sales were poor, and from a mintage of 125,000 each, only 17,500 of each specimen were saved from melting.

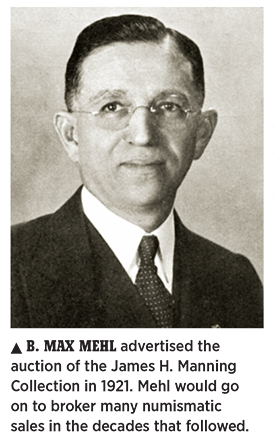

In other news, page 382 of the December 1903 issue of The Numismatist featured the magazine’s first advertisement, placed by teenager B. Max Mehl of Ft. Worth, Texas. He eventually became the most successful and famous rare coin dealer of his time, and remained so until passing in 1957.

A relatively new fad was the issuing of brass and aluminum tokens by coin collectors and dealers. Dozens of different varieties were made, and many were described and illustrated in print.

On another subject, it was stated that at the French Mint (Monnaie de Paris), the blasting of medals with fine sand at 180 feet per second gave them a pleasing “minutely granular or frosted” appearance. This pro-cess was carried over to the Philadelphia Mint and was used on proof gold coins from 1908 to 1915, much to the dissatisfaction of collectors.

Cream of the Crop

Heath tried to keep readers up-to-date on Association membership, elections (which typically were conducted at conventions, with some attendees holding many proxies from others) and other news, but information from the officers was sporadic and often incomplete. The October 1904 convention was held in St. Louis, with low attendance.

Each month, The Numismatist contained numerous classified advertisements. In the January 1906 issue, for example, J.C. Mitchelson, a prominent collector from Tariffville, Connecticut, took out space to state, “I cannot live without The Numismatist. It is the cream of my reading matter.”

In New York City, the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society announced that through a gift of railroad scion Archer M. Huntington, a property had been purchased on Audubon Terrace. There, a beautiful new headquarters, museum and library would be erected.

Old & New Favorites

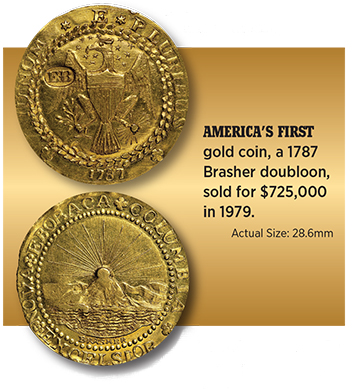

In February 1907, great American rarities were showcased in The Numismatist, including the 1787 Brasher doubloon; an 1822 half eagle (so rare that it had been given little publicity over the years); an 1804 dollar; and 1783 Nova Constellatio silver patterns. Colonials, Early American coins, copper cents, various tokens and medals, and old paper money continued to be marketplace favorites.

The 1907 convention was held in Columbus, Ohio, starting on September 2, at the Neil House. The Association had 421 members—a number that was more or less unchanged in recent years—of whom 28 went to the gathering, plus some spouses. It was supposed that the current ANA president Albert Frey would stand for re-election, but he surprised everyone by declining. This set in motion a series of fierce backroom deals by six or seven members who held about 250 proxies. Zerbe wielded significant influence and was elected president. (Dr. J.M. Henderson, a close friend of Zerbe’s and a resident of Columbus, was the convention host in charge of arrangements and activities.)

In autumn, the new Indian Head $10 gold coin designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, America’s most famous sculptor (who had passed away on August 3), reached circulation. A nationwide commotion arose in the press when it was baselessly stated that Mary Cunningham, an attractive Irish immigrant and waitress, was the model. More excitement was created in December, when the beautiful Saint-Gaudens High Relief double eagles (gold $20) with the date in Roman numerals were released. There was a great rush to buy them, and their price quickly jumped to $30 each.

Meanwhile, Baltimore collector Frank G. Duffield discussed at length the flaws in the proxy system used to elect ANA officers. The process encouraged abuse, and those chosen might not really represent the membership. Nevertheless, no specific charges were made in the 1907 election. Zerbe later countered Duffield’s sentiments in a three-page article.

Changing Ownership

ANA founder George Heath died on June 16, 1908. He was widely mourned and fondly remembered. In a communication dated Au-gust 1, 1908, ANA President Zerbe reported a conference with representatives of the Heath estate. He journeyed to Monroe, Michigan, during the third week in July, and spent three days completing arrangements for the immediate future publication of The Numismatist. Since the first issue, Heath had owned, edited and, for six years, personally printed the magazine, and later allowed the ANA to use it as its official publication. Zerbe and collector How-land Wood made arrangements to take it over, relieving the Heath estate from the obligations of fulfilling subscriptions. But Zerbe purchased the magazine, not on behalf of the Association, as many thought was the case, but for himself. As of January 1909, he published it in Philadelphia.

The 1908 convention (by then an annual event) was held in Phila-delphia from September 28 to October 2 at the Hotel Stenton, and Mr. and Mrs. Henry Chapman were the social hosts. About 30 of the 556 members attended. Wood proposed that the ANA constitution be revised to formulate a better method than proxies to determine elections, and Zerbe pro-tested. The discussion was at a stalemate, and it was agreed to keep the old system in place for another year. The still-influential Zerbe was re-elected president.

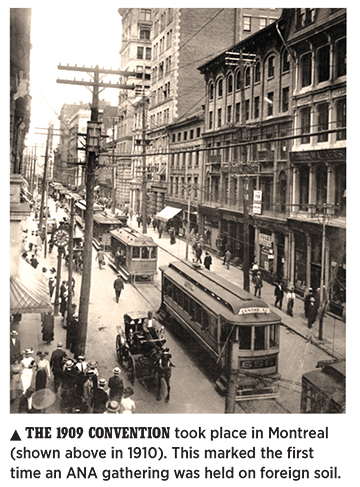

On August 9, 1909, the annual convention opened in Montreal, Canada—its first time outside the United States. Running for president were Francis C. Higgins, a well-known New York City collector, and Dr. J.M. Henderson. Mailings were made on Higgins’ behalf to blast Zerbe and Henderson. In retaliation, Zerbe sent out a mailing that declared Higgins unfit for office. Coming to Higgins’ defense was Thomas L. Elder, who called Zerbe out in print, stating, “How it must pain you to talk to anybody who does his own thinking. Your oily, oozy, slimy phrases will make about as much impression as a pea shooter against a belt of armor plate. Never again will the American collectors be deceived.” (Years later, it was discovered that Zerbe encouraged “phony” members to join for six months so he could gain their proxies.)

Close to 50 members attended the Montreal convention, about 450 proxies were exercised, and Henderson won the election. The enmity of Elder, Higgins and others continued against Zerbe, his personal ownership of The Numismatist, the hucksterism they felt characterized his numismatic activities at fairs and expositions, and his general dishonesty. In Zerbe’s favor was that under his aegis, The Numismatist had better articles, and more content and illustrations than ever before.

In-House Publishing

At the 1910 convention in New York City, ANA President Henderson was elected to a second term in a contest that was remarkably quiet. (Zerbe’s detractors seemed to have given up.) Zerbe sold The Numismatist to Canadian W.W.C. Wilson, who gifted it to the Association.

Around the same time, further steps were made to adopt an official standard for grading coins. In the ANA’s Year Book for 1910, Howland Wood proposed a grading system with these distinc-tions: Proof, Uncirculated, Very Fine (“condition but little below Uncirculated, with imperceptible wear or showing only under close scrutiny”), Fine, Very Good, Good, Fair and Poor. He also noted:

Nicks, scratches, corrosion, tarnish, marks, faults in striking and in the planchet, file marks, discoloration, spots, etc., should be stated in the description of every coin above Good. The color of the coins, especially copper coins, should be stated if the piece is of any value. Coins brightened by che-micals should not be called bright, but should be termed “cleaned.” “Bright” and “brilliant” are terms defining the natural condition of the coins, not an artificial rendering of the surface. The terms “evenly struck,” “off center,” “weak” or “strong impression,” should be used in every case when the value of the coin warrants the additional description.

The book was intended to be an annual issue, but the idea faded. (Alas, it was not until the 1970s that the ANA adopted official grading standards.)

By 1911, The Numismatist was edited by Albert R. Frey of New York City, with George H. Blake and Edgar H. Adams assisting. A new column, “Live American Numismatic Items” by Adams, became very popular and often included previously unknown information. Partly because of finances, the appearance of the magazine suffered a great set-back. There were fewer illustrations, and the typography was less imaginative than it had been under Zerbe’s command. This rather plain format would continue for many years.

In a style reminiscent of Heath’s earlier writing, author Frank C. Higgins wrote in his column, “Numismatic Elements,” that the main appeal of a coin was its history and artistry. In this era, the investment aspect of coins was taken for granted by advanced collectors, although occasional articles pointed out past successes.

In August 1911, Frey lamented that The Numismatist was the work of just a few people, and the greater part of the Association didn’t seem to care.

There are 27 names on the page of officers, Board of Governors, and district secretaries which is to be found in every number of The Numismatist. Of these not more than 12, or less than half those who are directly responsible for the prosperity of the Association, have taken the trouble to communicate with the editor since the January number appeared!

In December 1910, it was reported that there were 654 members, but by August of the next year, the number dropped to 553. The 1911 convention was held in Chicago starting on August 28, and about 50 people attended. The balance in the ANA treasury was $175.76. Around this time, there was an anti-dealer feeling among some members, and it was suggested that they not be allowed to serve in an ANA office or on the Board. Judson Brenner, an Illinois collector, was elected president.

Frey cashed in his chips and resigned in December 1911, stating he had suffered from misunderstanding and little support. By this time, ANA membership was declining, and it was not a happy time for the Association. Printing of The Numismatist was transferred to The Stowell Press in Federalsburg, Maryland, a firm that would produce the publication for many years after. The good news was that the highly accomplished and personable Edgar H. Adams was given the editorial chair. Classified ads, absent for a long time, also resumed.

A milestone in the history of the Association took place in 1912, when Representative William Ashbrook (D-Ohio), an ardent collector, introduced a House bill to give the ANA a rare federal charter. “We are informed that the bill was passed only after the hardest kind of three-hour fight,” said Adams. It went to the Senate, was approved and became law on May 12, after it was signed by President William Howard Taft.

For some time, there had been controversy within the Associa-tion as to what position had the most power: the presidency or the chairmanship of the Board of Governors. Other issues within the ANA included changing the bylaws and deciding whether dealers were desirable as members. In the meantime, The Numismatist remained far and away the major benefit to members, as only 15 percent of them attended the annual conventions.

Minute die varieties of federal coins were described in many articles over a long period of time—ranging from colonials and early cents and tokens to Morgan silver dollars and a series about small cents by U.S. Navy Commodore W.C. Eaton:

I have to now report that the Denver Mint is already using, or has used, three different dies for the cents of 1912. [A]t least the “D” has been cut in three slightly differing places. In the first two a prolongation of the “1” downward would cut the right edge of the “D” but in one case the “D” is perceptibly nearer the “9” than in the other. In the third variety the “1” prolonged would miss the “D” altogether and the “D” is smaller than in either of the first two varieties. These three varieties were all mixed in one lot of 25 I have just received from the Mint.

In August 1912, the annual convention was held at New York’s Hotel Rochester in the city of the same name. Membership stood at 550, 55 of whom attended the meeting. Judson Brenner was re-elected president. Adams reported that, unlike similar recent gatherings, the event was warm and friendly from beginning to end.

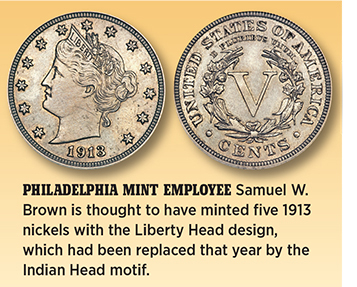

For the first time since its inception, The Numismatist was financially self-supporting, helped in part by $10-per-page advertising rates. (B. Max Mehl start-led Adams by running a two-page notice that year.) The Indian Head/Buffalo nickel by James Earle Fraser debuted to wide acclaim. Official production began on February 17. Meanwhile, an employee at the Philadelphia Mint, Samuel W. Brown, secretly struck at least five nickels with the old Liberty Head design, one in proof and four with a lusterous finish, igniting a numismatic frenzy that continues today.

Standardized Grading

Similar to Benjamin Franklin’s wry observation on weather, stand- ardized coin grading was a subject that was discussed endlessly, but no one did anything about it. Incoming president Frank Duffield stated that the Association would do well by adopting the system proposed by Howland Wood in 1910, but he “would not place the dealers under obligation to adhere to it in their catalogues, though this would be the object sought.”

The annual convention was held in Springfield, Massachusetts, on August 22-26, 1914, and all officers were re-elected. Members totaled 579, of whom 68 attended the gathering.

With a fond farewell, Adams resigned as editor of The Numismatist on July 28, 1915. Current ANA President Duffield was appointed to the post and served into the 1940s.

The 1915 convention was held in San Francisco from August 30 to September 1. Neither the president nor the vice president made an appearance. The gathering set a record for low member attendance. Some attributed this to widespread dislike for Zerbe, who was present at the show.

Troubling Times

The Great War in Europe (known as World War I) began in August 1914. By 1916, various medals had been issued by Germany, the aggressor, as well as by the British and other Allies. The Numismatist devoted much space to chronicling these pieces from 1916 through the end of the decade. Those produced by Karl Goetz in Germany had particularly innovative and often provocative designs.

The year 1916 was highlighted by the long-hoped-for issuance of new circulating coin designs. Sculptor Adolph A. Weinman created the Winged Liberty Head dime (nicknamed the “Mercury” dime) and the Walking Liberty half dollar, while Hermon A. MacNeil designed the Standing Liberty quarter. The coins were released near the end of 1916 to widespread acclaim.

While many factories ran day and night to supply war materials to Europe, the mints were busy stamping out large quantities of coins. Although commerce was robust, this activity did not translate to the hobby. At the annual convention held in Baltimore in September 1916, only 38 members attended, and it was reported that membership had declined to 482.

Acclaim for the 1916 coins continued well into 1917, when MacNeil modified the quarter to depict Liberty in a suit of armor, signifying military preparedness. That same year, America joined the war in Europe. Duffield resolved to record in The Numismatist as many as possible of the hundreds of medals that had already been issued by both sides and the pieces to come.

The 1917 convention was held in a familiar venue, the Hotel Rochester, August 25-29. Membership had increased to 512, with 80 members in attendance, and Carl Wurtzbach was elected president. Editor Duffield later commented that:

The increasing popularity of ANA conventions and their power to attract members from a radius of several hundred miles can be attributed to two reasons. First is the numismatic side, of course, for during the three or four days devoted to the convention one simply breathes a numismatic atmosphere…The other reason is that our conventions have become occasions for what may best be described as “a corking good time.”

The war continued until the armistice of November 11, 1918. In the May 1918 issue, Dr. Malcolm Storer’s article, “Numismatic Bibliography of the United States,” furnished a valuable list of periodicals and other informative sources relating to American numismatics. While by no means complete, it treated major citations from The American Journal of Numismatics, The Numismatist and other important references, although at the time, numismatic bibliophilia was of little interest to people outside of museums.

Later that month, the U.S. Department of the Treasury began melting 350 million long-stored silver dollars under the Pittman Act, so that the resulting bullion could be shipped to England, whose own supplies were short. No accounting was made of the quantities destroyed. A later generation of collectors surmised that the melt included many varieties that later proved to be rare, despite generous mintages.

The postponed 1918 convention was scheduled for Philadelphia, but canceled because of an outbreak of influenza. The 1919 convention was held October 4-8, 1919. President Wurtzbach reported that membership stood at just 489. “The number in attendance was about the same as at Rochester two years ago,” he stated. Waldo C. Moore, a prolific researcher and writer, was elected president for the coming year.

After the war, there was a general feeling that peace would result in a continuation of economic prosperity. The outlook for 1919 appeared bright. It was reported that in Europe, rare-coin auctions were setting records as pent-up reserves of buying power and enthusiasm were unleashed. In May, M. Sorenson proposed that a new silver dollar design be made to observe the victory in Europe. When such a commemorative became a reality in 1921, Zerbe claimed he thought of it first.

In July 1919, Duffield published “A Trial List of the Countermarked Modern Coins of the World,” the first in continuing installments that became the standard reference on the subject. Countermarks (or counterstamps) were placed on coins for many reasons, including the revaluation of a denomination; advertising; and vandalism. The initial series covered coins of Angola through Bolivia.

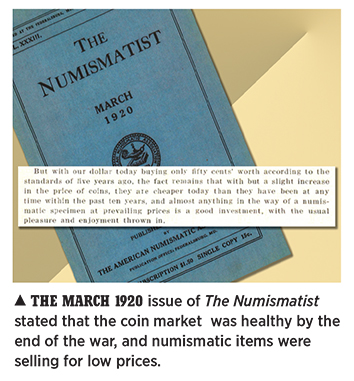

In March 1920, Duffield reflected that, unlike the prices of goods and services that rose sharply during the war, the coin market was relatively unchanged.

With our dollar today buying only fifty cents’ worth according to the standards of five years ago, the fact remains that with but a slight increase in the price of coins, they are cheaper today than they have been at any time within the past ten years, and almost anything in the way of a numismatic specimen at prevailing prices is a good investment, with the usual pleasure and enjoyment thrown in. The wise collector will not need to be urged to buy now to the extent of his ability.

The 1920 annual convention was held in Chicago, August 23-26, at the Hotel Sherman. Membership had increased to 603, and there was an aura of good feeling about the hobby and the market.

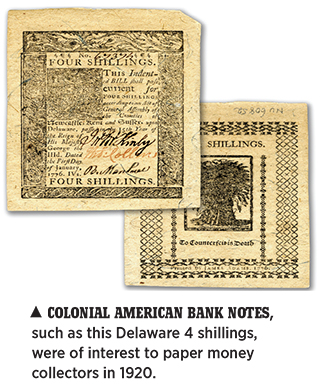

At the time, the most active collecting specialties in the United States were colonial and post-revolution coins; state coinage (popularized by a book by Hillyer C. Ryder and Henry Miller listing New England issues); Washington pieces; half cents (catalyzed by a book on the series by E.S. Gilbert); copper cents from 1793 to 1857; early silver and gold federal coins; patterns; and territorial gold.

Tokens of the early years through the Civil War had many advocates, as did Continental paper money, obsolete bank notes, fractional currency and Confederate paper. Interest in regular, large-size notes from 1861 to date was lukewarm and generally did not include notes from National Banks after the 19th century. Apart from U.S. issues, ancient coins were very popular, as were foreign issues and medals. Canadian coins were especially in demand.

As 1920 drew to a close, the Association and the hobby remained in good health, but more challenges were on the horizon.

Last month’s chronicle focused on Association highs and lows at the beginning of the 20th century. Businesses were growing rapidly, and coin production increased substantially at the start of the First World War. Continuing challenges included the lack of standardized coin grading and how to generate interest in the hobby. Despite the death of ANA founder George F. Heath in 1908, the future of the hobby was bright by 1921, and Association membership was climbing steadily.

Coin mintages reached rec-ord highs. In 1920 the Denver, Philadelphia and San Francisco Mints produced an unprecedented 809,500,000 pieces ranging from cents to half dollars. Silver dollars had not been struck since 1904. The postwar momentum ran out of steam, however, and in 1921, the call for consumer goods and services diminished, and coin production was sharply reduced from the spirited end of the last decade.

In the first ANA election of the new decade, only 203 members bothered to cast ballots. Moritz Wormser was elected president, succeeding Waldo C. Moore (a regular contributor to The Numismatist). The former would go on to serve a record six terms as president. Fred Joy won the post of first vice president; Frank H. Shumway, second vice president; and Alden Scott Boyer, treasurer. Six men were elected to the ANA Board of Governors.

As had been the case for many years, The Numismatist remained the primary benefit of ANA membership. Editor Frank G. Duffield continued his series, “A Trial List of the Countermarked Modern Coins of the World.” Attracting new faces to the hobby was desirable, and many articles gave suggestions for enticing new members.

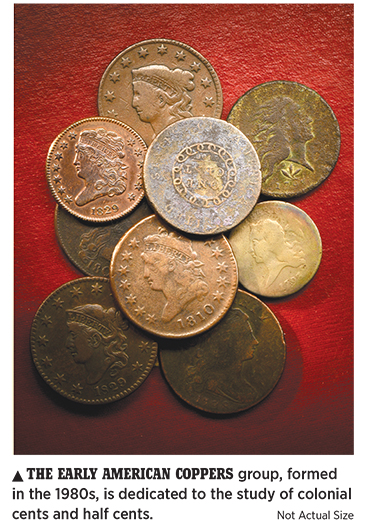

Popular collecting areas in the 1920s included colonial and Early American coins, with copper cents dated 1793 being a particular focus for collectors of die varieties. Vermont, Connecticut and Massachusetts state coins were in the fast lane as well, spurred by the release of State Coinages of New England (ANA Library Catalog No. GB80 .N44a) by the American Numismatic Society, which was comfortably situated in its temple-like headquarters on New York City’s Audubon Terrace. (This was in stark contrast to the ANA, which had no headquarters at the time.)

Tokens and medals also were favorites, with Civil War and Hard Times issues leading the pack. Federal coins were nearly always collected by date, as mintmarks were not particularly popular. Few people were interested in 1916-D dimes, 1901-S quarters and the like, and collectors would not discover the 1918/7-S quarter until 1931. (Looking through pocket change for potential finds was a rare pursuit.)

Commemoratives had a large following, and thousands of numismatists formed sets of the silver issues dating back to 1892. New commemorative half dollars were plentiful, including the 1920 and 1921 Pilgrim Tercentenary piece, 1921 Alabama and Missouri Centennial specimens, 1922 Grant Memorial issue, 1923-S Monroe Doctrine coin and many others. (Each of these received wide coverage in The Numismatist.) In 1926 the Oregon Trail series was launched, leading to more than a dozen date and mintmark combinations through 1939.

Gold commemoratives also com- manded great interest. (Lyman H. Low sold a 1915-S Panama-Pacific set with both types of $50 coin for $316.) There were no coin albums or holders available, and most collectors and dealers kept their treasures in paper envelopes measuring 2 x 2 inches.

On the Auction Block

Among the advertisers in 1921, B. Max Mehl announced the sale of the Honorable James H. Manning Collection, which included an 1804 silver dollar. Byrle B. Davis, a Los Angeles dealer, offered several varieties of privately minted gold coins, as well as other issues at fixed prices. Thomas L. Elder, trading as the Elder Coin & Curio Company, noted, “Our last sale brought over $15,000.” Wayte Raymond offered two price lists.

On December 7-17, 1921, Henry Chapman auctioned the John Story Jenks’ 7,302-lot collection, setting a record for bidder endurance, as sophisticated collectors and dealers felt compelled to examine every coin carefully. The sale brought $61,000, breaking the record for any coin auction ever held in America up to that time. Among the most active buyers was the cataloger himself, who advertised, “I bought largely at the Jenks sale, and if you are interested in any number, advise me which it is, and if I purchased it, we’ll price it.”

No guides listed market prices for coins, so this knowledge was gained by reading catalogs and advertisements, and tracking prices at auctions. As mentioned in last month’s article, there were no agreed-upon grading standards either, despite constant calls for such. One person’s Uncirculated might be another’s polished Extremely Fine (EF), resulting in much confusion.

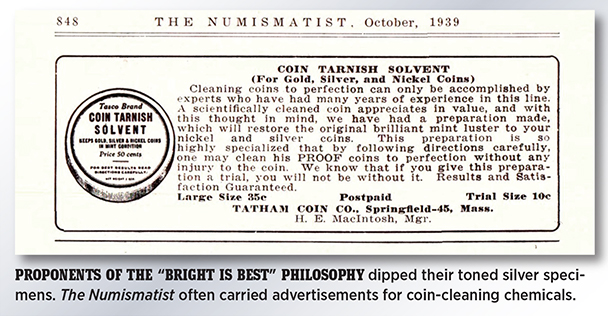

Clean & Bright

While it was perfectly fine to let copper coins mellow from orange-red to various shades of brown, and while gold pieces often remained mint-fresh in appearance, silver specimens had the nasty habit of tarnishing. (Heaven forbid!) Throughout this era, contributors to The Numismatist gave advice on how to keep coins bright. The Philadelphia Mint’s numismatic holdings (known as the Mint Collection) had been cleaned with silver polish several times. In his room at the Hotel Metropole in London on June 24, 1922, J. Sanford Saltus brightened his silver coins with potassium cyanide. This chemical, despite its lethal nature, was widely used. It not only removed tarnish, but also microns of metal from coins’ surfaces. Gone were tiny hairlines and evidences of friction. Saltus mistook a glassof the cleaner for ginger ale. The coroner reported, “Death by misadventure.”

America was prosperous in 1925, prices were rising and the outlook was rosy. Thomas L. Elder wrote that while an orchestra seat at a grand opera was $9,a prime sirloin steak was $3.50, and a skilled stonemason earned $16 per day, “I don’t believe that collector’s prices have kept pace with the prices of things in many other fields.”

Circulating Currency

Coins circulating in the 1920s included Indian Head cents dating back to 1859 and the occasional Flying Eagle cent dated even earlier. Nickels of the Shield, Liberty Head and Indian Head/Buffalo types were common, as were Barber and later-date Seated Liberty coins. Silver dollars circulated in some Rocky Mountain states, but hardly anywhere else. Half eagles (gold $5), eagles (gold $10) and double eagles (gold $20) were available at banks, but did not circulate in commerce. Quarter eagles (gold $21⁄2) were struck into 1915, then again from 1925 to 1929, but for some reason were not readily available at face value. The denomination was officially terminated in 1929, which had a positive effect a few years later.

Circulating paper money ranged in denomination from $1 and up, with $1, $5 and $10 bills being the most popular. A number of parallel series were in commerce, each backed by authorizing legislation specifying the amounts that could be issued. These included Legal Tender notes; Silver Certificates backed by silver dollars stored by the U.S. Treasury (accounting in part for large numbers of such coins being minted in the 1920s); Gold Certificates backed by gold coins; Federal Reserve Bank notes; Federal Reserve notes; and National Bank notes. The last were mainly the Series of 1902 and were paid out by thousands of banks across the country. If a bank failed, as some did, the notes were still backed by the Treasury.

Important Business

The ANA’s August 1921 convention was held in Boston’s Copley Plaza Hotel. Membership in the Association climbed to 704. The pending release of the new silver “Peace” dollar was a popular topic of discussion. Dealers were tolerated at conventions, but not widely welcomed. The buying and selling of coins was apt to draw cold stares.

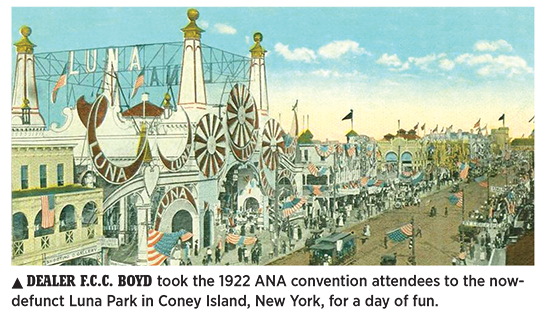

In August 1922, the ANA convention took place at the Great Northern Hotel in New York City. While dealing at such gatherings was frowned upon, it was typical to have an official auction. F.C.C. Boyd, who was rising rapidly in the ranks of dealers, conducted the affair. After the convention, Boyd hosted an evening at Coney Island, giving convention attendees tickets to Luna Park and other brilliantly illuminated attractions. (One couple was reported to have spent almost the entire time on the Honeymoon Express.)

The 1923 convention was held at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, a country that last hosted the show in 1909. The 1924 convention took place at the Hollenden Hotel in Cleveland, where it was announced that membership stood at 938. The auction, conducted by Henry Chapman, saw a 1793 Liberty Cap cent in Very Good grade sell for $33,a rare 1799 in Good for $16, and an 1839 Montreal side-view pennyin Very Fine grade hammer at $32.50. Entertainment one evening included a 30-piece saxophone band at Keith’s Palace Theatre.

The 1925 gathering was heldin Detroit, where a new high of 970 members was announced. At the auction, a “semi-proof” 1796 quarter sold for $20, an EF 1881 $3 piece went for $19, and a Lesher “dollar” issued by Boyd Park eclipsed these at $25.

In August 1926, members gathered in Washington, D.C., to spend several days exchanging views, giving programs, and buying and selling coins. Membership stood at 966.

Need for Books

In the early-to-mid 1920s, ample advertising space in The Numismatist attracted more collectors. During this decade, rare books and autographs brought record prices, as did Currier & Ives prints and other art. Julius Guttag offered an explanation as to the lassitude in numismatics:

Years ago the dealer gave freely of his knowledge and endeavored to educate the new collector as much as possible. Today many dealers make it their aim to keep the collector uninformed. During the past 20 years how many books or lists have been published by dealers? Outside of the books which Mr. Edgar H. Adams has issued, and through which interest in a new class of coins [patterns] has been stimulated, practically nothing of import has been contributed to our numismatic libraries.

If each and every dealer would show a live and honest interest in every new collector, encouraging him to join our Association, and perhaps the local numismatic club, I am sure it would not be long before a very live interest in numismatics would be revived. Further, a small pamphlet should be printed to give the history of coinage and the appeals of coin collecting.

It was true that books on Amer-ican coinage were few and outdated. Sylvester S. Crosby’s work on colonial coins was published in 1875, and had yet to be updated. The standard, but poorly compiled and uninteresting reference by J.W. Haseltine on early silver quarters, half dollars and dollars was issued in 1881. There was nothing of use on gold coins, early or modern. No publication featured mintage figures for coins from 1793 to date and, as noted, there were no price guides.

The Late 1920s

In 1924 the ANA launched National Coin Week, which in time became an annual tradition. Each issue of The Numismatist devoted at least a half page to numismatic societies and clubs. The usual report discussed coins and other numismatic objects that members brought for “show and tell,” as well as club business.

The 1927 convention was held in Hartford, Connecticut. Finally, membership crossed a magic line and stood at 1,002. The need for good numismatic publications was discussed, as was the idea that the ANA could create and publish new works, but this was rejected as being beyond the organization’s financial ability. Charles Markus was elected president, ending Wormser’s long and successful tenure. Elections, which had been very disruptive in previous years, were now quiet affairs—no name-calling, no defamatory pamphlets and no satirical tokens.

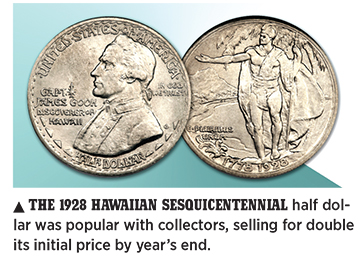

In 1928 the Hawaiian Sesquicentennial commemorative half dollar was released at a price of $2 and a mintage of 10,000. About half were sold in the islands, with the rest going to collectors. With-in the year, they were selling for $5!

In August 1928, the Hotel Seneca in Rochester, New York, hosted the convention. Area collector and dealer George Bauer showed color films via a new process developed by the local Eastman Kodak Company. (The product was not yet released to the general public, and caused a frenzy among convention attendees.)

The American economy was in overdrive in 1928. Skyscrapers were erected at a rapid pace in larger cities, art auctions set new records, luxury automobiles were all the rage, and many people could throw darts at a list of stocks, buy them and immediately make a profit.

In 1929 Raymond sold the regular edition of his book United States Gold Coins of the Philadelphia and Branch Mints (GB10 .R3u) for $1. The text was illustrated with six black-and-white plates and provided the retail values of all U.S. gold coins. No mintages were given, and historical information was virtually nonexistent.

M.L. Beistle of Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, who had started selling “Unique-brand” coin albums, published a new book on half-dollar varieties. New small-size paper money was issued to replace the large notes that had circulated since 1861. Record prices for certain coins, especially private and territorial gold issues, caused a stir in the auction room.

Although hardly anyone noticed, storm clouds were rising on the economic horizon in early 1929. The annual convention was held that August at the Congress Hotel in Chicago, and in October the stock market crashed.

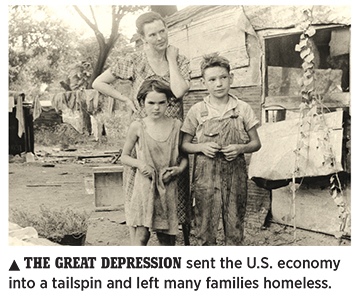

In early 1930, there was still hope that the stock market would recover. However, too much damage had been done. Margin calls were made, and investors were wiped out. Although projects already underway were continued—the Empire State Building and Radio City Music Hall being examples—new construction was put on hold. Thus began a steep decline that destroyed the U.S. economy and caused great suffering. Numismat-ics had not benefited from the great inflation of the 1920s. No one bought coins on margin or borrowed against them.

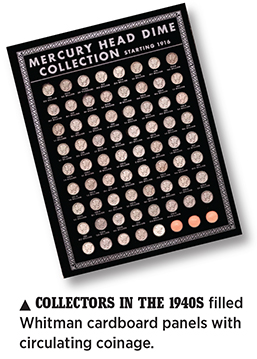

In 1930 the coin market remained stable. No one could have predicted that as the American economy went down, interest in rare coins went up! Raymond secured the distributorship of Beistle’s Unique-brand notebook-style coin albums, which sold untold quantities in the years that followed. Meanwhile, J.K. Post of Neenah, Wisconsin, introduced “penny boards” in 1934. It was great sport for many collectors to look through pocket change and fill the holes. Wisconsin-based Whitman Publishing took notice, bought Post’s business, and the rest is history.

Within a year or two, coins were no longer priced generically. The low-mintage 1909-S VDB cent was hard to find in circulation, and dealers’ stocks quickly dwindled. The date/mintmark tradition started in a large way and never stopped. The discovery of a previously unknown 1817/4 half dollar was reported in The Numismatist.

In the summer of 1930, the ANA convention took place at the Hotel Statler in Buffalo, New York, the site of the first large commercial installation of a Wurlitzer theatre pipe organ. ANA membership had increased to 1,196 names—a new high. The 71 new members that year included no youngsters, as the required age to join was 21. (Many unqualified applicants had been rejected.) Local and regional coin clubs were expanding rapidly.

The market also grew apace. A report of prices realized in Mehl’s December 9, 1930, sale showed strength in all areas, with prices considerably higher than they had been a year or two earlier. Among world and ancient coins, a 1656 gold broad of Cromwell, proof, brought $62.50, a 1671 5-guineas realized $36, and a stater of Alexander the Great in “practically Uncirculated” grade fetched $36. The sale realized a total of $30,803.71.

The August 1931 convention was held at the Netherland Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati. In his message, ANA President George J. Bauer said:

In the face of an economic condition that has not only strained the resources of individuals but governments as well and threatened the stability of our social structure, your Association has made steady progress and you will be pleased to learn that our membership in good standing has increased from 1,196 to 1,244, a net gain of 48.

Unknown Market

Because of the weak economy in 1931, coinage production was low. The only denominations struck were the cent, nickel, dime and double eagle. Mintages remained low in 1932 as well. The big news that year was the advent of the Washington quarter, replacing the Standing Liberty design minted from 1916 to 1930. The Tenino, Washington, Chamber of Commerce introduced wooden nickels, and the long-familiar “Don’t take any wooden nickels” phrase became a reality. Duffield commented:

Collectors of all series of coins cannot fail to have noted the increasing number of those who collect the small United States cents in the higher grades of preservation and the consequent advance in prices of Uncle Sam’s humble coin…Many of the collectors of large cents, who a few years ago would not go beyond 1857, have also added the small cent to their specialty. This demand has had the effect of boosting prices, and many small cents in Uncirculated condition are selling today for a greater price than some of the late dates of large cents. 25 years ago Uncirculated small cents could be purchased at auction sales in lots of assorted dates at about two or three cents each.

To accommodate collectors, the Treasury Department stated it had a variety of 1921-32 coins from the Philadelphia, Denver and San Francisco Mints available to collectors (for face value plus postage), including cents, nickels, dimes, quarters, half dollars, Morgan and Peace dollars, and eagles and double eagles. (Indeed, a 1927-D double eagle purchased for $20 plus postage in 1932 could be a million-dollar coin today!)

Improving The Numismatist was a hot topic of discussion. Some said it was fine as is, while others commented that it should be more scholarly, like the discontinued American Numismatic Journal. Perhaps the touché moment was furnished by a quip from Charles Markus: “I think The Numismatist should have nothing in it except learned discussions on the obolos of Lampsacus of Mysia.”

Goodbye Gold

In the summer of 1932, the quadrennial presidential election saw incumbent Herbert Hoover, famous for his “Recovery is just around the corner” comment, squaring off against Franklin D. Roosevelt, who promised a “New Deal” for America. Roosevelt won by a landslide.

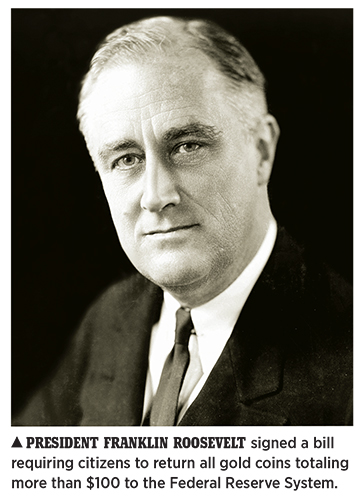

Inaugurated on March 4, 1933, Roosevelt set about making changes immediately. William H. Woodin, a longtime numismatist and student of patterns and gold coins, was named Secretary of the Treasury. Banks were failing left and right, and the Depression showed no signs of letting up. America’s gold reserves were being depleted by people who squirreled away “hard money.”

On April 5, 1933, Roosevelt decreed that private individuals had to return all gold coins totaling more than $100 to the Federal Reserve System before May 1 of that year. Exempted were “gold coins and Gold Certificates in an amount not exceeding in the aggregate $100 belonging to any one person; and gold coins having a recognized special value to collectors of rare and unusual coins.” This included all quarter eagles, as they had been discontinued in 1929 and had a premium value.

Anyone not complying was subject to a fine not to exceed $10,000; imprisonment not to exceed more than 10 years; or both. The regulation was subsequently modified to remove the $100 provision, thus making it illegal for ordinary citizens to hold regular (non-numismatic) gold coins. In August 1933, the annual ANA convention was back in Chicago at the Congress Hotel. Merriment, buying and selling, programs and other activities contributed to an enjoyable event.

In 1934 Roosevelt raised the price of an ounce of gold to $35, effectively stealing millions of dollars from citizens who turned in gold coins for face value. A part of America’s freedom had been abridged, and citizens could not trade common foreign gold coins minted after 1933, or bullion and Gold Certificates until 1974.

These gold regulations had a far-reaching effect on numismatics. Some collectors, including Louis E. Eliasberg Sr. and Floyd Starr, accelerated their purchases of scarce and rare gold pieces. Interest multiplied, and Charlotte and Dahlonega gold in particular increased in value. Popular gold dollars and $3 coins went up in price. Dozens of people started collecting double eagles by date and mint.